Hungarian-born pianist Géza Anda was born 100 years ago, on November 19, 1921. In his short life he achieved international recognition, particularly for his 1960s cycle of Mozart Concertos on the Deutsche Grammophon label; his reading of the Piano Concerto No.21 being used in the famous 1967 Swedish movie Elvira Madigan even led to that concerto taking on that moniker in popular culture.

But as is often the case, an artist’s most famous recordings might not reveal the full capacity of their capabilities. For me personally, it was coming across an early LP of Anda in a second-hand store that completely changed my perception of him as an interpreter. It was in my early years collecting in the late 1980s, and I found a record that I later found out had been his debut album for UK Columbia in 1953, the same label for which Lipatti had recorded until his untimely death in 1950. I’d been listening to Anda’s playing of the Mozart Concertos for years (my parents owned a few of the records), but I was certainly not prepared for the devil-may-care vivaciousness and jaw-dropping virtuosity so seamlessly fused with extraordinarily burnished phrasing that characterized his readings of Schumann’s Etudes symphoniques and the treacherous Brahms Paganini Variations. This performance of the Brahms demonstrates his incredible refinement fused with bristling excitement. With a jewel-like crystalline sonority, deft articulation, rhythmic vitality, and stunningly refined dynamic and tonal shadings, Anda delivers a reading that is simultaneously thrilling and elegant.

I soon realized that there was more to Anda than I had previously believed and I sought out all of his EMI recordings, usually coming across LPs on the American label Angel in my hometown in Montreal and original UK Columbia copies on my visits to London. All of the pianist’s discs from this period would over the course the 1990s be reissued on CD on the Testament label, with the notable exception of the Bach and Mozart 2-keyboard Concertos that he recorded with Clara Haskil, which were paired with his stunning Beethoven Piano Concerto No.1 on an EMI Références CD that was unavailable in North America (and which I obtained by mail order in those pre-internet days).

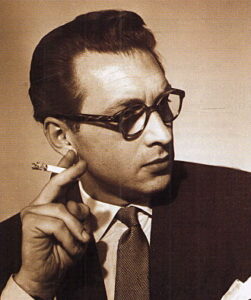

Around this time I spent a year studying with Charles Reiner, a Hungarian-born pianist based in Montreal. I had met Reiner in 1989 because in his youth he had had some lessons with Dinu Lipatti just before the legendary artist had to retire due to the illness that then killed him, and I was just beginning my obsessive research into the pianist at that time. In our conversations about great pianists, Reiner mentioned Anda: being Hungarian seemed to mean that he could always introduce himself to any compatriot backstage, regardless of how famous they were, which Reiner did when Anda played in Montreal. He told me about meeting him each time he visited for concerts and how his colleague simply couldn’t stop smoking, a habit that sadly led to his untimely death in 1976 at the age of 54. Another memory of Reiner’s has stuck with me all these years: he still recalled hearing Anda for the first time on the radio in 1942 – nearly 50 years earlier – when the young pianist gave his Budapest debut, playing the Brahms Second Concerto with Mengelberg conducting.

Around this time I spent a year studying with Charles Reiner, a Hungarian-born pianist based in Montreal. I had met Reiner in 1989 because in his youth he had had some lessons with Dinu Lipatti just before the legendary artist had to retire due to the illness that then killed him, and I was just beginning my obsessive research into the pianist at that time. In our conversations about great pianists, Reiner mentioned Anda: being Hungarian seemed to mean that he could always introduce himself to any compatriot backstage, regardless of how famous they were, which Reiner did when Anda played in Montreal. He told me about meeting him each time he visited for concerts and how his colleague simply couldn’t stop smoking, a habit that sadly led to his untimely death in 1976 at the age of 54. Another memory of Reiner’s has stuck with me all these years: he still recalled hearing Anda for the first time on the radio in 1942 – nearly 50 years earlier – when the young pianist gave his Budapest debut, playing the Brahms Second Concerto with Mengelberg conducting.

Around the time that Reiner told me of that performance I came across a broadcast recording of Anda playing that same Concerto dating from a dozen years after the Mengelberg performance: a 1954 German radio tape issued on an Italian ‘pirate’ label that published unofficial radio and concert recordings. I was transfixed by what was the most perfect performance I had heard. Everything was there: gorgeous tone, burnished lines, fluid phrasing, incredible power, rhythmic vivaciousness. He had not recorded this work while under contract to EMI but did later for DG and to my ears the playing simply wasn’t of the same standard: this 1954 account with Klemperer conducting was just unbeatable. (It has been reissued in the last decade in a fantastic remastering from the original radio tapes – unconditionally recommended!)

Thus began my interest in this incredible pianist, yet another whose most famous recordings I could tell did not do full justice to his capabilities. Fortunately as the CD era progressed, and then the internet, recordings that had once been out of print or available only to well-connected collectors became publicly available. In the early 90s, I had on DAT (Digital Audio Tape) some of Anda’s other German broadcasts that had been shared with me from some international collectors, including five concerto recordings produced at the Südwestfunk in Baden-Baden (which I had visited in person in 1990 to collect a tape copy of Lipatti’s Bartok Third Concerto) and other stellar performances; all of these are now readily available on CD as well as on the internet. Nevertheless, I believe that Anda is still worthy of more exploration and recognition for the true nature of his stupendous music-making.

Thus began my interest in this incredible pianist, yet another whose most famous recordings I could tell did not do full justice to his capabilities. Fortunately as the CD era progressed, and then the internet, recordings that had once been out of print or available only to well-connected collectors became publicly available. In the early 90s, I had on DAT (Digital Audio Tape) some of Anda’s other German broadcasts that had been shared with me from some international collectors, including five concerto recordings produced at the Südwestfunk in Baden-Baden (which I had visited in person in 1990 to collect a tape copy of Lipatti’s Bartok Third Concerto) and other stellar performances; all of these are now readily available on CD as well as on the internet. Nevertheless, I believe that Anda is still worthy of more exploration and recognition for the true nature of his stupendous music-making.

For a pianist who lived a mere 53 years, Anda left behind a massive discography over a thirty-plus year period. His first discs were for Polydor starting in 1942 – the year of that fabled Brahms 2nd with Mengelberg – and reveal instantly a truly individual and intelligent artist. His May 1943 account of the Chopin Etude Op.25 No.5 is one of the most arresting recordings of the work ever made: he plays at a spacious tempo that never drags thanks to the attentive care with which he caresses each phrase, luxuriating with sumptuous nuances that are nevertheless neither self-indulgent nor sentimental.

Also in May 1943 Anda made his only official recording with orchestra that decade, a superb traversal of Franck’s Symphonic Variations, a work of which no later performances by the pianist appear to exist. (He had played it in January of that year with Furtwängler, who on that occasion referred to Anda as a ‘troubadour of the piano’ – a moniker that has been used for the pianist ever since.) Accompanied by Eduard van Beinum conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra (a recording made in Amsterdam, whereas his others at the time were produced in Berlin), he certainly does play with lyrical freedom but also with the poised voicing, clarity of articulation, and refined dynamic shading that would characterize the best of his playing – masterful music-making by the 21-year-old pianist!

Not yet under a fixed recording contract, in 1947 Anda recorded Brahms’s Three Intermezzi Op.117 and the Intermezzo Op.119 No.2 in France for the BAM (boite a musique) label, performances not reissued on LP to my knowledge and only now for the first time reissued on CD in an anniversary set produced by DG for the pianist’s centenary (click here).

While Anda matured quite wonderfully from the early performances here, there is some fine playing, with balanced voicing, beautiful tonal colours, and natural rubato. His tempo in Op.117 No.2 will appear brisk to contemporary ears, but it’s about the same tempo Lipatti played at in his early test recording of the work. Clearly the record was well received: it was awarded a Grand Prix du Disque.

In 1950 and 1951, Anda produced a number of recordings for the Telefunken label, among them his first account of Schumann’s Carnaval and second of the Etudes symphoniques. His complete discs for that label were compiled into a superb single CD exemplary in every respect by the wonderful Audite label (more on them below when it comes to Anda’s broadcasts), including one of his rare accounts of solo Bach and what appears to be his only recording of a solo Mozart work. While the entire playlist is on YouTube (click here), it is a phenomenal release well worth obtaining for discerning Anda fans, not least for the insightful text that gives some tantalizing details: apparently Anda left the label in 1952 due to issues with distribution as well as the technical quality of the recordings, and as a result did not record some of the works slated for production, including Gaspard de la nuit – a work of which no broadcast recording by Anda has been found or issued…. what a loss!

Anda’s records for the label still feature some fabulous playing of works not found elsewhere in his studio releases, among them a marvellous Haydn Sonata played with his characteristic deftness of articulation, rhythmic vitality, and beauty of tone, appreciable despite the rather dry acoustic of the studio.

That Anda’s repertoire was broader than his studio output is clear from the enticing insight that he had played Gaspard, but fortunately a similar treasure that he didn’t officially recorded did survive: a 1952 account of Ravel’s Piano Concerto for Left Hand, the first of his five concerto recordings made at the Südwestfunk radio station in the 1950s under the leadership of the great Hans Rosbaud. Anda was at his fiery best, playing with a massive dynamic range, a varied tonal palette, beautifully refined nuances, and masterful pedalling – and wonderfully supported by Rosbaud.

It must have been a boon to producer Walter Legge to have the fiery and equally photogenic Hungarian pianist sign to EMI Columbia after his departure from Telefunken, given that Legge’s star pianist Dinu Lipatti had died at the end of 1950. Anda’s debut album, as introduced earlier, is a jaw-dropping account of the Brahms Paganini Variations and the Schumann Etudes symphoniques, his third account of the Schumann in only a decade (he had set one down for Polydor in 1943 prior to his 1950 version for Telefunken).

The EMI recording was made on April 23 and 24, 1953 at Abbey Road Studio No.3 using the wonderfully responsive Steinway 299 used in that studio by Lipatti, Cortot, Moiseiwitsch, Fischer, Schnabel, and other legendary pianists. This may be the most successful of his four studio traversals (there’s also a 1963 DG account, plus several concert and studio broadcast recordings): his exquisite array of tonal colours, incredible dynamic gradations, magical pedalling, precise and varied articulation, and remarkable sense of rhythm are all captured marvellously by the recording engineers.

Anda was widely recognized for his Bartók, having left behind a legendary account of the complete works for piano and orchestra for Deutsche Grammophon in the late 50s and early 60s, but his phenomenal EMI traversal of the composer’s For Children is far less known. Recorded January 4-6, 1954 (Book 1) and January 8-9, 1955 (Book 2), these performances reveal the artist’s absolute craftsmanship: the fluid lyricism of Anda’s phrasing is utterly beguiling, with a masterful use of varied articulation (one of the hallmarks of his playing at this period), incredibly refined dynamic gradations, gorgeous tonal colours, and phenomenally subtle pedalling.

Anda so successfully avoids any banging or harshness of tone in music that is usually subjected to such abrasiveness: he once stated that “if one understood what a musical phrase means, there was no longer any difference in the approach to music between Mozart and Bartók,” and his playing here bears this out. This is truly astounding pianism that demonstrates that ‘easy’ music is not necessarily easy to play well – even if it sounds it.

The exquisite beauty of his playing in these works makes one wish he had recorded the complete solo Bartók works but unfortunately he did not. Fortunately, however, two unofficial recordings exist of Anda playing the glorious Suite for Piano Op.14, a stupendous radio broadcast account issued by the Audite label in their series of superb Anda broadcast performances and this hair-raising Edinburgh Festival concert performance from 1955 issued on BBC Legends. While this concert recording is sonically inferior to the German broadcast, musically it is beyond reproach, demonstrating Anda’s beautifully defined articulation, remarkably precise rhythmic pulse, transparent voicing, and marvellous conception of the work. The characterization of each movement is magnificently accomplished.

While Anda and Karajan were both signed to Columbia at the same time, they never recorded together during this period. However, they appear to have collaborated extensively in 1954, with at least two concerts in Italy that year, playing the Bartók Third Concerto in Torino on February 12 and on December 11 for a Brahms B-Flat Concerto in Rome. They would record the Brahms together in 1967 after they had both moved to Deutsche Grammophon – in fact, it appears that it was the fact that Anda wanted to record this work with Karajan for Columbia that was one of the reasons he was dissatisfied with the label (Hans Richter-Haaser was chosen to record the work instead).

However, the two never recorded any Bartók together in their time at DG, Anda having already recorded the composer’s complete piano/orchestra works with Fricsay for the label between 1959 and 1961. This Torino performance of the Bartók Third Concerto finds both Anda and Karajan on top form, with a wonderful rapport and marvellous precision yet also warmth and vitality. The pianist’s crisp articulation, glowing sonority, rhythmic steadiness, and beautifully refined dynamic gradations serve the lyrical nature of this opus wonderfully.

This August 22, 1956 concert recording with Anda playing Bartók’s Piano Concerto No.2 at the Lucerne Festival with his compatriot Ferenc Fricsay conducting captures to perfection the excitement of the music and the unified nature of their great collaborative relationship (there’s another exceptionally exciting 1952 broadcast with the two musicians available on an Audite CD that I can’t recommend highly enough and they would over the course of their lives play this work together some 60 times!

In this Lucerne performance, Anda plays with tremendous rhythmic drive as well as a balance of crisp articulation and wonderful pedal effects, once again demonstrating that one need not bang or produce a harsh sound while playing Bartók. The rapid section of the middle movement is absolutely hair-raising in its intensity, yet even here Anda never produces an abrasive sound – stunningly exciting and beautiful playing!

Here is one of his less-known recordings: a marvellous account of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.1 in C Major Op.15, with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Alceo Galliera, set down at EMI’s Abbey Road Studio No.1 on February 2 and 5, 1955 – his only solo EMI concerto recording not reissued by Testament.

This incredible recording finds him playing with a stunningly beautiful tonal palette, remarkably buoyant and precise rhythmic pulse, crisply defined articulation, and refined dynamic shadings. One quality that’s in evidence in this performance is how each note is crystal clear and articulated with jaw-dropping precision, yet the tone for each note also glows – this combination of consistent articulation and tonal beauty is utterly unique to anything I’ve heard by any other artist… truly remarkable! Incomparable playing – my desert-island recording of this work!

In April 1956, Anda produced a magnificent recording of Bach’s Concerto for Two Keyboards in C Major BWV 1061 together with Clara Haskil, with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Alceo Galliera (they also recorded a Two Piano Concerto by Mozart – also gloriously played). There is marvellous ensemble between the soloists and with the orchestra, and the two pianists play with a wonderfully vibrant rhythmic pulse, gorgeous tone, and crystal-clear voicing.

His performances of Liszt were fascinating if somewhat unconventional. Anda recorded the Liszt Sonata in B Minor for EMI in 1954, a reading that is very individual in its emphasis on elegance over virtuosity, a performance that I find to be quite different from any other. A broadcast from 1955 is even more arresting than the studio account, and fortunately this is among the Audite releases (click here). I had been given a cassette copy of this by a German collector in the 90s and listened to it nonstop, and its current release is exceptional. Gorgeous tone, crystalline articulation, wonderfully sculpted phrasing, and nuances and timing that clarify to perfection both the architecture and emotional content of the work.

Here is a glorious unissued November 25, 1956 concert recording of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.1 with Anda accompanied by Paul Paray and the New York Philharmonic – the artist’s Carnegie Hall debut from the second of over a dozen tours he would have in the country. Anda made a commercial recording of the work for EMI the previous year, but this live reading has more raw intensity while retaining the distinguished elegance that is so characteristic of his pianism. What a beautifully polished sonority, arched phrasing, wonderfully coordinated articulation, and refined nuancing!

Anda brought distinguished elegance to his performances of the full range of repertoire, making his readings of works traditionally considered to be ‘showpieces’ quite fascinating. His EMI account of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No.1 is a superb reading, surpassed in intensity and bravura (while still retaining its charm) by a volcanic 1958 broadcast recording with Solti conducting (reissued with that incredible Brahms 2 with Klemperer).

This film footage – apparently filmed in 1964 – features excerpts from the first and third movements of the work and finds the pianist even at this different phase of his career playing with his trademark polish and refinement. One hopes that a complete filmed performance will be issued.

For more film footage, there is this wonderful documentary that shows Anda teaching, playing, and listening to recordings – almost always with a cigarette in hand or mouth. If only it were translated into English! Nevertheless, some fantastic archival footage and insight into the musician and the man.

To close this tribute, one of my all-time favourite piano recordings by any artist: Anda’s stunningly beautiful January 1954 reading of the Delibes-Dohnányi Valse Lente from Coppélia. Recorded on that marvellous Steinway No.299 at Abbey Road under the supervision of Walter Legge, this performance is one of the most charming and pianistically accomplished recordings ever made:

Anda plays with an amazing array of tonal colours and dynamic shadings, remarkably refined use of pedalling, incredible timing (including a few tongue-in-cheek nuances), masterful nuancing, mindful articulation, burnished phrasing … the list could go on and on. Stay tuned for that harp-like effect at the end after those gorgeous trills – you’ve probably never heard anything like it! Magical pianism!

Despite his tragically short life, Géza Anda left behind a massive recorded legacy of studio recordings on multiple labels as well as a wealth of unofficial concert and radio recordings. Posterity is indeed fortunate to have such a rich array of glorious performances by this superb musician.

One comment

I was so grateful to be able to read your wonderful article about Geja Anda, which I love so much.