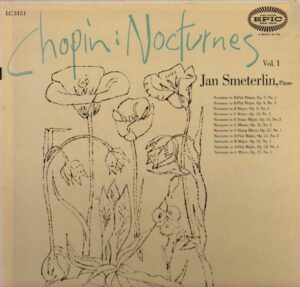

I am delighted to have written the liner notes for a superb new release of Jan Smeterlin’s incredible 1954 recording of Chopin’s Nocturnes, which also features some other recordings in the two-disc set. Here is my text included in the CD booklet, along with some photographs from the production and the complete playlist at the end of this post:

It is hard to imagine a time when multiple recordings of the most popular classical works were not available at a moment’s notice. However, even as bulky shellac 78rpm discs gave way to long-playing records around 1950, many of the great masterpieces were unavailable or underrepresented in the catalogue. It may come as a surprise to even the most ardent piano fan that the first cycle of Chopin’s twenty Nocturnes was recorded by the Philips label in 1954 featuring Jan Smeterlin, a Polish pianist largely unknown today.

Leopold Godowsky recorded twelve Nocturnes in 1928, and then the legendary Arthur Rubinstein produced the first ever volume of nineteen in 1936–37, followed by a second version in 1949–50. Smeterlin was the first to present twenty Nocturnes on disc. Guiomar Novaes and Nadia Reisenberg also featured twenty in their 1956 cycles, as did Stefan Askenase in 1957, but other mid-1950s accounts by Peter Katin and Alexander Brailowsky only had nineteen. (The Opus posthumous Nocturne No. 21 appears not to have been included until Ingrid Haebler’s 1960 Vox set.) Smeterlin’s small discography has surely contributed to his not receiving the enduring adulation afforded his compatriot Rubinstein, and his less charismatic delivery was also possibly not as appealing to the general public. There is no doubt, however, that this release of Smeterlin’s Chopin reveals top-tier pianism.

He was born Hans Schmetterling in Bielsko, Poland on 7 February 1892, changing his name to Jan Smeterlin in 1924. He had his first lesson at age seven, and the following year played a movement of a Mozart concerto in public, performing Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasia two years after that. Although his father had him study Latin and Greek, he also pursued music training with Theodore Vogel, an organ pupil of Bruckner, who hoped that the young boy would become a conductor. His lessons consisted largely of playing through two-piano reductions of symphonies, operas, and chamber music, which surely helped him develop his lyrical approach at the keyboard. Smeterlin attended lots of concerts and stated that listening to singers deepened his awareness of fluid phrasing and organic timing, while hearing orchestral music brought an appreciation of texture and colour.

Vogel was not the only one with firm ideas about Smeterlin’s path: the boy’s father wanted him to follow in his footsteps as a lawyer, so he sent the seventeen-year-old to Vienna to study at the university there. In doing so he unwittingly helped his son with his own goal of becoming a musician: Jan had already hoped to go to that city to study with the legendary Godowsky, so once there he auditioned and ‘miraculously’ was accepted in his master class. The small group of fifteen included others who would go on to great careers, such as the great Russian pianist and teacher Heinrich Neuhaus and conductor Issay Dobrowen. Marvelling at how Godowsky had not two hands but ten fingers that served him faithfully, the young pianist learned an approach to polyphony that fortified his earlier training with orchestral scores.

Though he performed at Bechstein Hall (later Wigmore Hall) in London alongside other Godowsky pupils in 1912, his career would be stalled until after World War I, during which he served in the Polish cavalry. Smeterlin survived that ordeal, as well as some health challenges, before his 1920 debuts in Warsaw, Vienna, Berlin and Paris. His tours would take him around Europe as well as through North America, Latin America, Java, Australia and New Zealand. He settled in London with his British wife Edith (Didi), a cello pupil of Felix Salmond. Their home was furnished with exotic souvenirs from his tours and became a gathering place for visiting musicians such as Arthur Rubinstein, Edwin Fischer, and the Schnabels. After his October 1930 debut at Carnegie Hall, Smeterlin would continue regular tours across America for some 30 years, living in New York for some time before returning to London shortly before his death on 18 January 1967 at the age of 74.

While he came to be seen as a Chopin specialist, Smeterlin stated that Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata and Bach’s Goldberg Variations were his ‘musical bible’, adding that he ‘would feel greatly impoverished if I had to live without Schubert, Mozart, Haydn, Brahms, and many impressionist composers’. Early in his career, he had embraced the oeuvre of his contemporaries Szymanowski, Scriabin, Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Dukas, and Albéniz, premiering many of their works locally and receiving dedications. As he performed more extensively in major venues worldwide, critical acclaim for his Chopin led to his including more of the composer’s works in his programs.

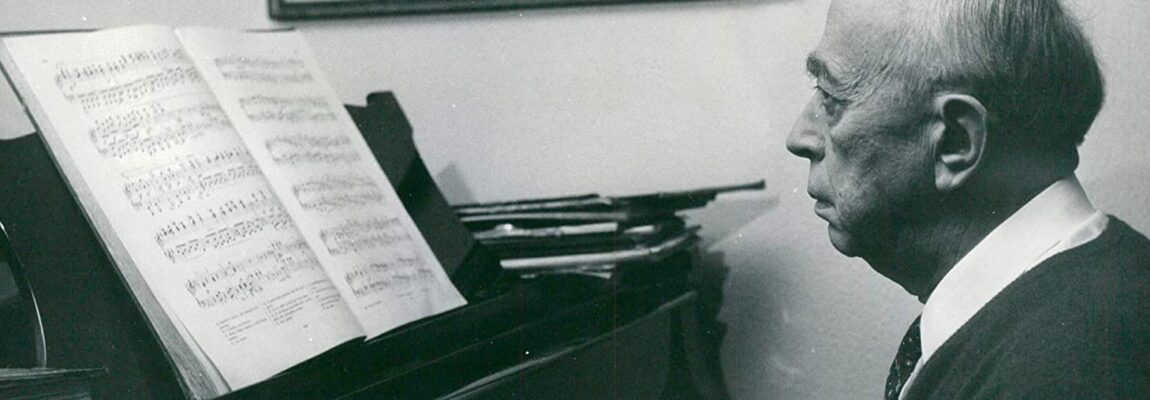

By the time he recorded his cycle of Nocturnes in 1954, Smeterlin was internationally known as a Chopin pianist. An Australian critic’s comment that he had ‘the Chopin touch’ aroused a spirited ongoing discussion in the local media as to what the term meant. The artist himself responded that although many believe that there is a fixed sound to each instrument, it is in fact the interpreter who creates his unique timbre. Even more important than the physical skill required to crafting one’s tone was ‘to come away from the keyboard; leave pianistic problems alone for a while and think how you wish a work to sound … touch begins in the mind, the heart, the musical consciousness. It cannot be mastered through piano practice alone’. However, his writings make it clear that he had a remarkable understanding of the actual mechanics involved in producing a beautiful sound. The combination of his masterful technique and musical imagination yields a magnificent array of sonorities put to intelligent musical use.

Smeterlin’s Nocturnes are like watercolour paintings, colourful without being garish, atmospheric without being overly impressionistic. His tonal palette is varied and skilfully polished, his textures transparent. His interpretations have an incredible sense of spontaneity: one never knows if he will play softly or loudly, whether he will slow down or accelerate, but his choices always sound natural, each phrase fluidly forged like a master actor shapes words into sentences filled with meaning in order to express the depth of the text being communicated.

He was not one to shy away from burnishing a melodic line, yet at no time does Smeterlin’s playing sound forced even when at its most impassioned. Never is his inflexion exaggerated, his tone harsh, his nuancing extreme. Some of the naturalness in his playing comes from his striking balance of time and rhythm. He stated that ‘too automatic an adherence to time is apt to kill the more important quality of rhythm’, which he defined as ‘freedom within time: one note is shortened, another prolonged’. He so seamlessly adjusts pacing and the balance between melodic line and accompaniment that the rigid bar lines of the text dissolve in the fluidity of his rubato and suppleness of his phrasing (some particularly fine examples can be found in his delivery of the Nocturnes Op. 9 No. 3, Op. 32 No. 1 and Op. 62 No. 1). This expressive device commonly employed in the nineteenth century, and which can sound idiosyncratic in the hands of lesser pianists, seems completely natural here. One can also easily overlook the fact that Smeterlin often plays with dynamic markings opposite to those in the score, never sensing he is disrespecting the spirit of the work under his fingers. As Dinu Lipatti said, ‘If you carry yourself well, you can put your feet on the table and no one will think anything of it.’

Our appreciation for Jan Smeterlin is bolstered here by the first ever release of a BBC recital and an unpublished Decca recording. His BBC appearance on 17 April 1949 includes six Mazurkas, the kind of works that his intimate pianism serves best. In his native Poland, Smeterlin had seen the mazur folk dance performed excitedly in rural settings and elegantly in ballrooms, which surely contributed to his idiomatic sense of rhythmic impulse and accenting in these charming but deceptively difficult works. We also have a rare opportunity to hear him in two of Chopin’s most heroic compositions, the First and Fourth Ballades. Smeterlin eschews any excess without sacrificing grandeur, playing boldly but without brashness, sensitively without lapsing into sentimentality.

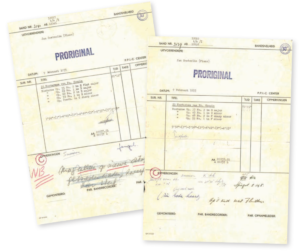

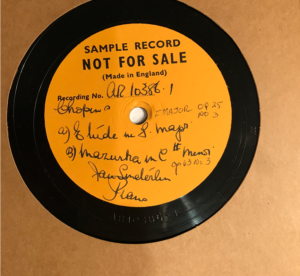

At two June 1946 sessions at Decca’s West Hampstead Studios, Smeterlin cut a few Chopin records that were never issued. The music recorded at these sessions included three Mazurkas, two Waltzes, two Études and the B-flat-minor Scherzo. All were presumed lost until a single test pressing of one side was uncovered in his collection at the International Piano Archives at Maryland. This reading of the F-major Étude and the Mazurka, Op. 63 No. 3 (Smeterlin segues the pair) are characterised by the same grace, nobility and refinement as the other performances on this collection, making these discoveries a welcome addition to his discography.

We live at a time that the esteemed Chopin and Liszt biographer Alan Walker has dubbed ‘The Age of Anonymity,’ adherence to the text being so ingrained in our musical culture that many performers limit the range of expression in their readings, while a handful impose their persona such that it risks overriding musical content. With a style that was paradoxically individual and unobtrusive, Jan Smeterlin brought sumptuous and highly personal nuancing to his playing while avoiding even a hint of ostentatious showmanship. The recordings issued here are a model of sensible, sensitive pianism that shows that personality need not eclipse a composer’s creation – a balm to soothe the soul of the 21st-century Chopin lover.

Below is the first track in the entire release (you need click here for the full playlist – my website won’t embed it). Click this bold text for an online retailer providing international deliveries

And a bonus upload: a 1966 Mace label LP, released in the last year of Smeterlin’s life, featuring more Chopin recordings – a very rare release, never reissued. While his dexterity was slightly more compromised at this time, the playing is extraordinarily poetic and his tone is absolutely marvellous. Many thanks to Mike Gartz for digitizing this vinyl and to Neal Kurz for the noise reduction.

Comments: 2

Click on the image of the test pressing, there is a series of 4 additional images that are not indicated on my screen.

Actually the images are within the article, but when displayed as a slide show are larger. I suspect it comes up if you click on any of the images. I’m learning…