Among the most remarkable aspects of recorded history is the capacity to hear both composers and those who were associated with them play some of the most beloved music ever written. It is particularly insightful when we can hear skillful musicians who had worked with composers giving performances that are radically different in style from what has become the norm today, providing access to perspectives of interpretation that cannot only be gleaned from the score. These pages have featured the playing of Ilona Eibenschütz, who had studied with Clara Schumann and coached with Brahms, and another great pianist who had also worked with these two legends stayed before the public and active as a teacher for a much longer time: the German pianist Carl Friedberg.

Early years

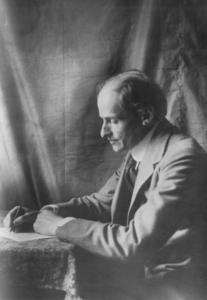

Karl Rudolf Hermann Friedberg as born September 18, 1872 in Bingen, Germany into a Jewish German family of wine merchants living in the area since 1700. At the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, he studied with both James Kwast (a Reinecke pupil) and Clara Schumann. He was advanced enough that he began teaching piano at the age of 16 as he continued to hone his craft. Friedberg would become not only a proponent of the Schumann school but also that of Brahms, whom he had met at Clara Schumann’s home when he was about 16, turning pages for the composer on at least one occasion.

Karl Rudolf Hermann Friedberg as born September 18, 1872 in Bingen, Germany into a Jewish German family of wine merchants living in the area since 1700. At the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, he studied with both James Kwast (a Reinecke pupil) and Clara Schumann. He was advanced enough that he began teaching piano at the age of 16 as he continued to hone his craft. Friedberg would become not only a proponent of the Schumann school but also that of Brahms, whom he had met at Clara Schumann’s home when he was about 16, turning pages for the composer on at least one occasion.

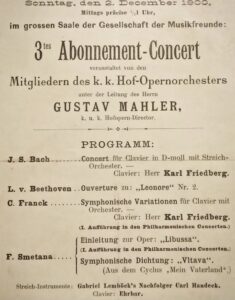

Friedberg’s official debut was on December 2, 1900 with the Vienna Philharmonic under no less than Gustav Mahler, playing Bach’s D Minor Concerto and Franck’s Symphonic Variations, a performance that was positively reviewed by the legendary critic Edward Hanslick. He had not nearly a decade earlier given a historically important performance that has slipped under the radar, when at age 19 he stood in for Eugen d’Albert in the second performance of Strauss Burleske (which d’Albert had premiered in 1890), learning it from the manuscript in 24 hours.

Coaching with Brahms

As an established 21-year-old artist, Friedberg played an all-Brahms recital in 1893 that was attended by the composer (unbeknownst to the soloist), who was sufficiently impressed that he invited the pianist to coach with him on how to play his works. As Friedberg himself would later recall,

As an established 21-year-old artist, Friedberg played an all-Brahms recital in 1893 that was attended by the composer (unbeknownst to the soloist), who was sufficiently impressed that he invited the pianist to coach with him on how to play his works. As Friedberg himself would later recall,

“I saw him when I first came to Vienna; he came to my Brahms recital, the Brahms evening [November 7, 1893]. I did not know that he had attended the concert, or I would have died of fright. I played the F Sharp Minor Sonata; two books of the Paganini Variations, four of the Eight Piano Pieces, Opus 76; the Six Piano Pieces, Opus 118; the Two Rhapsodies, Opus 79; and some of the Waltzes. But not the Handel Variations; I have never been so fond of them as the Variations on an Original Theme. I liked those much better. He came back after the recital and invited me to the Tonkunstler Verein for a celebration that night of Ignaz Brull’s birthday [a Viennese pianist-composer and close friend of Brahms]. And we sat there and celebrated the occasion with food and drink. Then [Brahms] took me to the Imperial Coffee House – he never wanted to go to bed early and he didn’t say one word about my recital until three o’clock in the morning. Then he stroked his beard and said, ‘You know you played very wonderfully, young man, but you mustn’t do that again. You mustn’t play a whole evening of Brahms. People don’t like that; they don’t want me. I am not yet popular enough. Play other things and only one work of mine – you do me a better service.’ The humility of that, to say he wasn’t popular enough, that they would not like to hear only Brahms! And I had received great applause; I said the applause is due to you, Mr. Brahms, not to me.”

When Friedberg asked Brahms for insights into how to play his works, the composer mumbled, “I don’t give piano lessons.” But soon after, they went to his home, the composer brewed some coffee and opened up a bottle of his favourite cognac, and after the two had some drinks, the composer sat at the piano and began to go through all of his solo piano works … with the exception of the Paganini Variations, which was technically beyond the composer at that age. Friedberg stated that “he paused only now and then to pick up a pencil to jot down new and more definitive marks of expression than the published editions indicated. He took pains to explain certain intricacies, to interpret different readings.”

It is fascinating to hear Friedberg decades later in recordings made during lessons with his pupil Leonard Hungerford (who later changed his name to Bruce) describing that at times Brahms did things that might sound to be in poor taste in the mid 20th century and that he (Friedberg) did not particularly like, adding that he did not find that composers could always play works at their absolute best:

Establishing a career

Friedberg divided his time between teaching and performing, excelling at both. He first taught from 1893 to 1904 at the Hoch Conservatory where he had trained, then at the Cologne Conservatory from 1904 to 1914, before his 23-year post at Juilliard in New York (called the New York Institute of Musical Art when he began) from 1923 to 1946. It is still the topic of conversation that “for the best interests of long-term over-all planning” Friedberg was unceremoniously removed from his post at Juilliard when new management came in, leading the pianist to say simply, “They don’t need me any more.”

Friedberg divided his time between teaching and performing, excelling at both. He first taught from 1893 to 1904 at the Hoch Conservatory where he had trained, then at the Cologne Conservatory from 1904 to 1914, before his 23-year post at Juilliard in New York (called the New York Institute of Musical Art when he began) from 1923 to 1946. It is still the topic of conversation that “for the best interests of long-term over-all planning” Friedberg was unceremoniously removed from his post at Juilliard when new management came in, leading the pianist to say simply, “They don’t need me any more.”

As a performer, Friedberg was equally active in solo, chamber music, and concerto appearances. His American debut was a Carnegie Hall recital on November 2, 1914; two weeks later he played there at a Concert for the Benefit of German-Austrian-Hungarian Relief, and then the following month played the Schumann Concerto with the New York Philharmonic. He remained in the US during WWI, finally returning to Germany in 1918 but continuing to visit the US to perform and teach, before moving there to assume his post at Juilliard.

A beloved teacher

Friedberg was adored by his pupils, with Hungerford stating that he could never tire of studying with him and could have gone on doing so forever. Malcolm Frager was equally enamoured of his kindness and insightful teaching (Friedberg had once not only bought him a ticket for a Horowitz concert, but included a dollar with the ticket so that the young man could taxi safely home). Other pupils of note included William Masselos (considered to be one of the strongest proponents of the Friedberg style), Nina Simone (!), William Browning, and Elly Ney.

Friedberg was adored by his pupils, with Hungerford stating that he could never tire of studying with him and could have gone on doing so forever. Malcolm Frager was equally enamoured of his kindness and insightful teaching (Friedberg had once not only bought him a ticket for a Horowitz concert, but included a dollar with the ticket so that the young man could taxi safely home). Other pupils of note included William Masselos (considered to be one of the strongest proponents of the Friedberg style), Nina Simone (!), William Browning, and Elly Ney.

The late Joseph Banowetz studied briefly with Friedberg starting at the age of 17 and recounted to me with great enthusiasm before his own death earlier this year his encounters with the great German pianist. At his first lesson he played Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C Minor and a few variations in he was stopped as Friedberg asked, “What is this crazy stuff you are doing? You’re changing the rhythm and doing all kinds of things.” When Banowetz explained that he admired Rachmaninoff’s recording and was copying some of his playing, Friedberg exploded, stressing that one should not copy, that this was not in the Beethoven style, and that he should be respectful first to what is in the score. Apparently Clara Schumann had lost her temper with the teenage Friedberg for not paying attention to dynamic markings in the score, and this first lesson of Banowetz’s was the only time he recalled Friedberg losing his temper that way, for the same reason of fidelity to the score. The rest of their lessons were far more even-tempered and Banowetz retained a lifelong admiration for Friedberg.

Friedberg’s pianism

Despite his emphasis on attention to the score, there is nothing dry or academic about Friedberg’s playing, or is there is any lack of individuality in his performances. As heard in the recorded sample above, he objected to changes of note values but not the use of rubato or dramatic timing. His playing is also characterized by an exquisitely beautiful sound at all levels of his massive dynamic range; in an interview published in the January 2, 1915 edition of Musical America, Friedberg stated that “the tone an artist draws from his instrument should be round, full and expressive, capable of being shaded and varied, just as is the bel canto of the singer. We should learn to sing with our fingers.” He added, “I believe in making everything musical, in always making the tone beautiful, even in technical exercises and scales. The piano is more than a thing of metal and wood; it can speak, and the true artist will draw from it wonderful tones. It should be part of his constant study to create beautiful tone. I believe a single tone can be made expressive.”

Hearing Friedberg both teach and play the Brahms Ballade in G Minor Op.118 No.3 is an opportunity to appreciate his incredible insights into the works of Brahms – and what power in his performance from his July 24, 1951 Juilliard recital (remastered and available on St. Laurent Studios here – the recordings of him teaching have not been issued but some can be heard on the Arbiter website here.) Not only is the playing of the 78-year-old pianist daring and blazing to the point of being volcanic, it is incredibly expansive in phrasing and adjustments to tempo according to the musical content. Even as he stretches phrases, he never loses the line nor the pulse; while these adjustments to timing can sound unusual to modern ears, they are, in fact, aligned with the structure of the composition and how the composer expected such nuancing to be employed.

Commercial and unofficial recordings

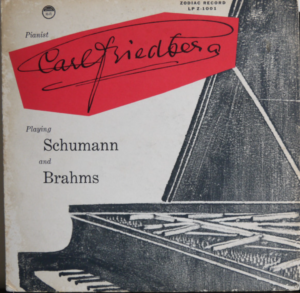

Friedberg had long resisted making recordings because he disliked the sonic limitations of the medium (he also disavowed the piano rolls he made) while also finding the concept of a fixed, permanent interpretation to run counter to his philosophy of musical communication. He was finally convinced to preserve some performances on disc in 1953, when at the age of 81 he set down an LP for Zodiac Records (LPZ-1001), which was issued in two separate pressings. There was sufficient material not sanctioned for release that would be made available some 30 years later on a 2-LP set produced by the International Piano Archives at Maryland, and whatever reservations the pianist may have had about the medium, there are some stupendous performances to be found in these accounts.

Friedberg had long resisted making recordings because he disliked the sonic limitations of the medium (he also disavowed the piano rolls he made) while also finding the concept of a fixed, permanent interpretation to run counter to his philosophy of musical communication. He was finally convinced to preserve some performances on disc in 1953, when at the age of 81 he set down an LP for Zodiac Records (LPZ-1001), which was issued in two separate pressings. There was sufficient material not sanctioned for release that would be made available some 30 years later on a 2-LP set produced by the International Piano Archives at Maryland, and whatever reservations the pianist may have had about the medium, there are some stupendous performances to be found in these accounts.

As gorgeous as Friedberg’s playing is in his studio recordings, there is an extra degree of freedom that can be heard in existing private recordings: two Juilliard recitals (1949 and 1951), as well as a few excerpts from broadcasts of solo recitals and a full 1951 Toledo performance of the Brahms B-Flat Concerto; some of the solo performances were issued alongside the Zodiac recordings on a set on the Marston Records label (CDR versions of the sold-out set are available from Marston here). Other solo and chamber broadcasts were issued on some Arbiter releases dedicated to artists who knew Brahms.

The clip below features a number of performances from his commercially issued LP (presented here with the original crackle of the worn vinyl): Schumann’s Kinderszenen Op 15 (0:08) and Novellette in D Major Op.21 No.4 (17:51), followed by the Brahms Scherzo Op.4 (21:32), Intermezzo Op.76 No.4 (30:34), and a composition by Friedberg himself (36:34). Throughout we hear his gorgeous tonal palette, magnificent legato phrasing, exquisite nuancing, and – when required – impressive power.

This superb performance of the Schumann Romance Op.28 No.2 is another that showcases Friedberg’s gorgeous singing tone, disarmingly direct phrasing, natural timing, and beautiful transparent textures. His absence of sentimentality and his chaste use of rubato can seem almost off-putting to listeners more used to the more overt use of expressive devices (and it’s not like Friedberg never used these – his Chopin is remarkable for such nuancing, as will be heard below) but he highlights things quite differently in this reading, letting the music speak for itself.

A broadcast performance of Friedberg playing Beethoven’s Sonata No.27 in E Minor Op.90 is an extraordinary document that demonstrates how fiery and impassioned the artist could be in concert even at a more advanced age. In his late 70s, Friedberg plays with a depth of tone and fiery passion that are almost startling, all the while sustaining beautifully sculpted melodic lines, voicing chords with incredible clarity, and playing with incredibly expressive timing while maintaining the pulse.

At his July 24, 1951 Juilliard recital, Friedberg played a Chopin Nocturne of which there are not many historical recordings, the A-Flat Major Nocturne Op.32 No.2. A few months shy of 79 at the time of the performance, he plays with a beautifully sculpted melodic line, with inner voices unobtrusive but clearly highlighted, and his rubato is fascinating – and what gorgeous tonal and dynamic control in the last minute! Utterly beguiling!

This 1949 broadcast recording of Chopin’s Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor Op.44 finds the 77-year-old Friedberg playing with volcanic passion and intensity that many a younger pianist would aspire to, fused with both intelligence and emotional depth. The towering octaves and booming bass notes are wonderful tempered by an exquisitely burnished melodic line, and Friedberg’s use of dynamics to build tension and timing to hold the listener in rapt attention are absolutely masterful.

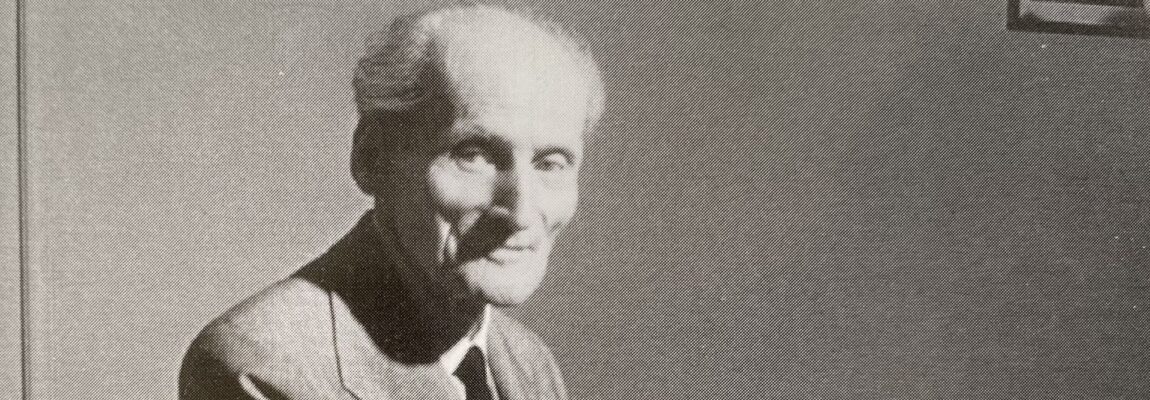

Finally, quite a miraculous recording: a November 7, 1951 concert performance of Friedberg in Brahms’s Piano Concerto No.2 in B-Flat Major Op.83 with the Toledo Symphony Orchestra conducted by Wolfgang Stresemann, which was recorded by Bruce Hungerford on the same tape machine he used to preserve his lessons with the pianist. At age 79 Friedberg plays with impressive power, authority, and dexterity, despite a memory lapse in the opening of the first movement. His dynamic range is impressive, and he phrases expansively with long melodic lines. The photograph included with this video was taken at this concert. Quite an extraordinary historical document!

Comments: 2

It’s a great tribute to a beautiful pianist Mark, thank you so much!

Outstanding work, Mark – many congratulations. And how superbly you’ve curated the audio extracts and recorded performances. An important document for anyone interested in performance practice, not just the tradition that derived from the Clara Schumann/Brahms circle.