Dinu Lipatti is justly celebrated for his performances of Bach. He had a remarkable capacity to vary the attack used by different fingers even within the same hand so that the voicing of each line was thoroughly consistent, to a degree rarely heard in other artists. Contrapuntal parts therefore sounded as though they were being played by different instruments, each line sounding like an individual voice with its own unique timbre, together highlighting the structure of the score in stunning detail while infusing it with warmth and life.

Dinu Lipatti is justly celebrated for his performances of Bach. He had a remarkable capacity to vary the attack used by different fingers even within the same hand so that the voicing of each line was thoroughly consistent, to a degree rarely heard in other artists. Contrapuntal parts therefore sounded as though they were being played by different instruments, each line sounding like an individual voice with its own unique timbre, together highlighting the structure of the score in stunning detail while infusing it with warmth and life.

Lipatti himself spoke to Bach’s music being the closest to his heart, and it is most unfortunate that he did not record more than his miraculous take of the B-Flat Partita and four transcriptions. He was in fact scheduled to commit to disc four Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier at the Geneva sessions in July 1950 that produced his most celebrated recordings of Bach, Mozart, and Chopin, but he sent the engineers home two days early, ostensibly because he wanted to give the EMI technicians a break, but most likely because he himself was exhausted from the ordeal of 10 days of recording as the temporary effects of the cortisone being used to treat his Hodgkin’s Disease started to fade.

There are few fans of Lipatti’s playing who would not wish for more recordings of him playing Bach, and there have been tantalizing leads. A rather disturbing one is the story that Lipatti’s biographer Grigore Bargauanu was at a Swiss radio station where the card catalogue showed that a studio-made disc of a Prelude and Fugue was in the collection, but when he and the archivist went to get it, it was missing from the stacks.

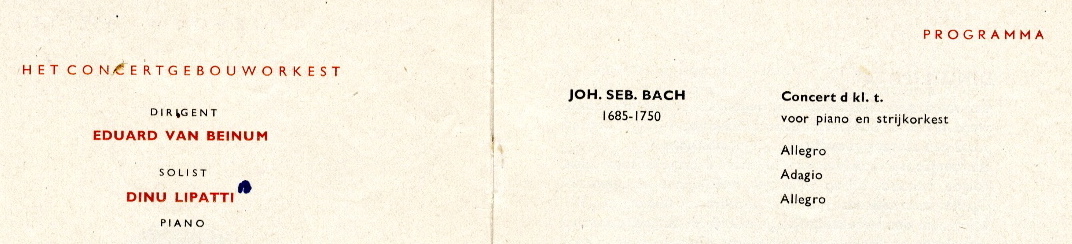

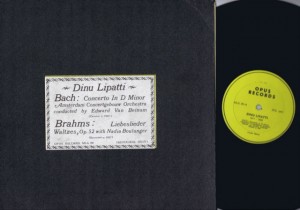

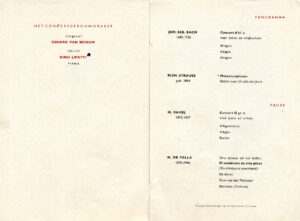

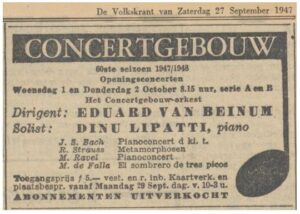

Around 1972, Opus Records released an LP of Lipatti performing the Bach D Minor Concerto with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Eduard van Beinum on October 2, 1947. The flip-side of the disc was Lipatti’s 1937 recording with Nadia Boulanger and her troupe of singers of Brahms’ Liebeslieder Waltzes Op.52, which had never been issued in LP format by EMI. No notes indicated the provenance of the live recording.

Around 1972, Opus Records released an LP of Lipatti performing the Bach D Minor Concerto with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Eduard van Beinum on October 2, 1947. The flip-side of the disc was Lipatti’s 1937 recording with Nadia Boulanger and her troupe of singers of Brahms’ Liebeslieder Waltzes Op.52, which had never been issued in LP format by EMI. No notes indicated the provenance of the live recording.

Opus label releases were produced by the International Piano Archives, which was run by Gregor Benko, who informed me that he had obtained the tape of the performance in an exchange with a Swiss collector by the name of Marc Fleury. At the time that they traded tapes (though the Bach was originally recorded on acetates), Benko was unaware of the fact that Lipatti had played the Ravel G Major Concerto at the same concert (Lipatti had in fact played the same program on both October 1 and 2). He lost touch with Fleury and so it is unknown if the Ravel performance also survived in his collection. The prospect of that recording existing, given Lipatti’s exceptional commercial disc of Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso, is certainly an exciting one. Despite the Dutch radio archives having a remarkable collection of their concert history preserved on disc, even the Bach seems not to exist in their library.

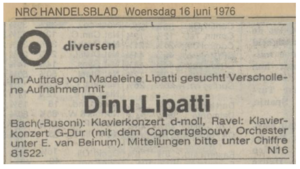

This record appeared without either the pianist’s widow Madeleine Lipatti or recording producer Walter Legge having previously known about it: Legge first heard about it via one John Jessett, who was fascinated with Lipatti and had tried finding whatever unpublished recordings of the artist he could (sadly Jesset did not live to see the current riches that are now available). Legge informed Madeleine about the Opus Records release, and she then placed advertisements in Dutch newspapers hoping for leads to the source material of the Bach and also the Ravel Concertos (even after the Bach had been issued), but sadly with no success.

This record appeared without either the pianist’s widow Madeleine Lipatti or recording producer Walter Legge having previously known about it: Legge first heard about it via one John Jessett, who was fascinated with Lipatti and had tried finding whatever unpublished recordings of the artist he could (sadly Jesset did not live to see the current riches that are now available). Legge informed Madeleine about the Opus Records release, and she then placed advertisements in Dutch newspapers hoping for leads to the source material of the Bach and also the Ravel Concertos (even after the Bach had been issued), but sadly with no success.

This Bach Concerto recording is one of the most unusual recordings of Dinu Lipatti to have surfaced, as it reveals aspects of the pianist’s artistry that are inconsistent with how he is usually perceived. Lipatti is often held up as a pianist who held the score as sacrosanct, despite the fact that he made changes to the score in his Alborada disc and his concert performance of Schubert’s E-Flat Impromptu. He himself stated that fidelity to the Urspirit of a score, as opposed to the Urtext, was his priority: “Far be it for me to promote anarchy and disdain for the fundamental laws which guide, along general lines, the coordination of a valid and pertinent interpretation,” he wrote in notes for a planned Interpretation course to be co-presented with Nadia Boulanger. “But I find it a grave mistake to lose oneself in researching useless details regarding the way in which Mozart would have played a certain trill or grupetto…wanting to restore to music its historical framework is like dressing an adult in an adolescent’s clothes. This might have a certain charm in the context of a historical reconstruction, yet is of no interest to those other than lovers of dead leaves or the collectors of old pipes.” Note that Lipatti did not say we should not pay attention to these details but rather emphasized that we should not lose ourselves in them – that the music should still be primary.

This Bach Concerto recording is one of the most unusual recordings of Dinu Lipatti to have surfaced, as it reveals aspects of the pianist’s artistry that are inconsistent with how he is usually perceived. Lipatti is often held up as a pianist who held the score as sacrosanct, despite the fact that he made changes to the score in his Alborada disc and his concert performance of Schubert’s E-Flat Impromptu. He himself stated that fidelity to the Urspirit of a score, as opposed to the Urtext, was his priority: “Far be it for me to promote anarchy and disdain for the fundamental laws which guide, along general lines, the coordination of a valid and pertinent interpretation,” he wrote in notes for a planned Interpretation course to be co-presented with Nadia Boulanger. “But I find it a grave mistake to lose oneself in researching useless details regarding the way in which Mozart would have played a certain trill or grupetto…wanting to restore to music its historical framework is like dressing an adult in an adolescent’s clothes. This might have a certain charm in the context of a historical reconstruction, yet is of no interest to those other than lovers of dead leaves or the collectors of old pipes.” Note that Lipatti did not say we should not pay attention to these details but rather emphasized that we should not lose ourselves in them – that the music should still be primary.

Lipatti’s approach to the D Minor Concerto is so radically unconventional that it paints him as more of a firebrand than his somewhat staid reputation as a literalist and pianist of ‘purity’ might indicate. Lipatti uses some of the variants in Busoni’s edition of the concerto, among them passages where arpeggios occupy two octaves instead of one (or answer in a higher octave a statement in a lower one) and bass register notes are played lower than Bach wrote them. Lipatti’s rhythm is remarkably steady and his accenting pronounced, though the emphasis never breaks the line. His articulation is varied, he is more liberal with the pedal and the highlighting of left-hand figurations, and he makes some rather dramatic ritardandos.

The first movement is among the most fascinating performances that exist by Lipatti, with a number of passages in particular demonstrating his unusual conception of this work. The section from 5:22 to 5:44, where arpeggios are extended and played with the most delightful inner rhythmic pulse, is magnificent. Perhaps the most incredible moment begins at 6:39, where he starts a phenomenally graduated decrescendo that brings the audience to complete silence as he highlights a downward chromatic progression, creating a melting effect until his playing goes down to a whisper at 7:02 – miraculous.

This concert recording captures Lipatti’s playing at its peak (he was in relatively good health) and it is an important part of his discography. Despite its early appearance on IPA’s Opus Records label and subsequent releases on Jecklin and Turnabout/Vox, EMI did not issue the recording as part of Lipatti’s official discography. They had explored the possibility in 1981 but, as they often did, shied away from negotiations with orchestras and conductors that were signed to other labels. Finally in the year 2000, when they had realized that they had not prepared a commemorative release for the 50th anniversary of the pianist’s death, they accepted a proposal that I had initially made in 1991 to release this performance with the Liszt E-Flat Major Concerto and Bartok Third Piano Concerto. The disc was issued early in 2001 and these three concerto performances are now part of Lipatti’s official EMI discography.

Let us continue to hope that the recording of the Ravel G Major Concerto will surface, as it will surely be a stunning performance that also paints a different portrait of Lipatti’s pianism and interpretative genius.