American pianist Raymond Lewenthal was born 100 years ago, on August 29, 1923. The brilliant musician had a difficult life and never had the consistent recognition that his artistry warranted – he was a sensation in the UK but less so at home in the US – and sadly he died prematurely due to a chronic heart condition at the age of 65 in 1988. Fortunately he left behind a significant legacy of recordings, including an array of studio discs and concert recital and concerto performances, all revealing pianism of tremendous musicality and emotional expansiveness.

Born in San Antonio, Texas, Lewenthal had a challenging childhood. His father left when he was five, and when he was eight his mother moved the two of them to Hollywood, where Lewenthal did some work as a child actor under the name Rémond Duval (he appeared in A Tale of Two Cities). He was apparently exposed to the highly individual artistry of Ervin Nyiregyhazi while in LA (prior to the fabled pianist’s disappearance for some decades) and he started his piano lessons at the late age of 15, first with Moriz Rosenthal pupil John Crown and then with Lydia Cherkassky (mother of Shura) before receiving a full scholarship to study at Juilliard with Olga Samaroff. Her influence was both personal and professional, and her introduction of her young charge to Dimitri Mitropoulos was an important one: the conductor wrote an open letter of recommendation in which he addressed the young man’s ‘great pianistic talent and musicality’ and he booked him to play Prokofiev’s Third Concerto – a work that he himself usually played while conducting.

Lewenthal was soon offered management and played a Town Hall debut in New York, in addition to making appearances throughout the country. His Carnegie Hall debut of October 30, 1951 was recorded and is an important recorded testimonial of his artistry, finding the pianist in his early years in a wide range of repertoire. There is much to admire here: a gorgeous array of tonal colours, attentive voicing and use of articulation to clarify architecture, beautiful pedal effects, rhythmic vitality, and lots of spontaneous touches (including a few regrettable but exciting memory lapses in the Liszt Sonata). While the Beethoven Op.109 is a bit ‘direct’ for me, the grandeur and individuality on display throughout the recital are inspiring.

Here is a July 11, 1952 broadcast of Lewenthal playing Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.1 in E-Flat Major that captures his youthful vigour and idiomatic approach to the composer’s writing, a wonderful listen despite a few coordination issues between soloist and conductor.

Lewenthal’s success would sadly be short-lived: on August 3, 1953 he was accosted and beaten in Central Park, suffering several broken bones – including his hands. It took him years to recover both physically and psychologically, by which time his name had faded from memory. Fortunately he was able to secure a contract with the Westminster label, for which he produced four LPs, among them a superb album devoted to Toccatas spanning several centuries – here is his account of the Czerny Toccata in C Major Op. 92.

After recording his Westminster albums, Lewenthal was able to go to Europe to have some training with his idol Alfred Cortot (in whose teaching he was disappointed) and also with Guido Agosti, whom he would later declare to have been his best all-around teacher. In 1960 he received what appeared to be a great invitation to be director of a conservatory in Brazil, but it was only when he arrived that he discovered that the institution did not yet exist, that he was expected to create it from the ground up, and that there were no funds for either a salary or his already-incurred travel expenses. It took him some time to be able to pay his way back to New York, by which time his mother had just died.

He did play while in Brazil, and a recording exists of him playing on August 29, 1960 – his 37th birthday. Here is his account on that date of Liszt’s Three Petrarch Sonnets:

And on the same occasion, he gave this towering traversal of Liszt’s titanic Sonata in B Minor – a work he sadly did not record commercially:

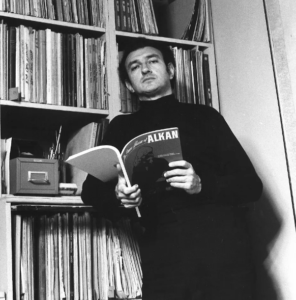

In 1963, Lewenthal gave a two-hour presentation on the WBAI radio station in New York about the music of Alkan, a composer who had fascinated him since his teens: Samaroff was a pupil of Alkan’s son Élie-Miriam Delabord and Lewenthal would include some of the obscure composer’s works in his Westminster recordings. The broadcast resulted in a contract to record an Alkan album for RCA, which would also lead to other recordings for the label. The WBAI program can be heard in several parts on YouTube: the entire playlist can be accessed by clicking here – the first clip can be heard on this page by clicking the image below.

Lewenthal’s career was back on track as he made many successful appearances, among them a stunning September 22, 1964 recital at Town Hall in New York. This recording captures the event in very good sound quality (not studio quality but still excellent) and his interpretations are simply glorious. Lewenthal’s fusion of technical brilliance and musical depth is a shining example of how technique can be used for musical purposes: his sonority is always beautifully polished, lines elegantly sculpted, and textures clear, while rapid passages are simply dazzling in their evenness of articulation and staggering speed.

While RCA invited Lewenthal to record some of the obscure repertoire that fascinated the pianist, he was also enthralled by Liszt and set about recording the Années de Pelerinage (which he had been featuring in his recitals for years), but for some reason the project was abandoned partway through: he recorded Years 1 and 2, which were never published at the time, and Year 3 went unrecorded. Finally in 2019 Sony Classical (in charge of the RCA back-catalogue) published the two unreleased albums as part of a box set devoted to Lewenthal’s complete recordings on RCA and Columbia, and the playing is absolutely phenomenal.

Below is the first work from Year 1 – the entire playlist for that album can be heard by clicking here, while the full playlist for the Second Year can be accessed by clicking here. Kudos to Lewenthal’s pupil Walter Winterfeldt and musicologists Farhan Malik and Don Manildi for their work on the now regrettably out-of-print box set that includes the world premiere release of these superb performances.

As much as Lewenthal was being praised at home, his reception in the UK was on a whole other level, with audiences lined up around the block for tickets. A magnificent document of his playing at the time is a favourite amongst collectors of pirated tape performances, a February 5, 1967 Belfast recital that features transcendent pianism. What a massive dynamic range, rich array of tonal colours, attentive and transparent voicing (that deep resonant bass is remarkable), intelligent pedalling (appreciable despite the somewhat echoey amateur recording), and grandly shaped phrasing. The fact that Lewenthal opens with the towering Alkan Symphony for Solo Piano speaks volumes to his stamina and temperament! Hold onto your hat(s) with the Mephisto Waltz, an absolutely scorching traversal that is one of my all-time favourite readings of the work.

Lewenthal was a leader in what would be termed the Romantic Revival with his focus on obscure works from the 19th century. Ever the showman, he set the tone for musical experiences from a bygone age through his dramatic choice of wardrobe (there are many photos of him in a cape and top hat) and atmospheric effects with subdued lighting. But he was no ‘mere’ showman, his technical command always serving an inspired and intelligent musical vision, with equal parts dazzling dexterity and sensitive nuancing. Here is the pianist in a marvellous 1970 concert performance of some of the obscure music he favoured: Lyapunov’s Piano Concerto No.1 and the third movement of Scharwenka’s Piano Concerto No.2 (he was less enamoured with the first two movements, apparently), with the Butler University Symphony Orchestra. Even with the sound quality of this amateur recording we can appreciate his gorgeous singing sonority, massive dynamic range (without any loss of tonal quality), marvellous timing, and refined shadings.

Lewenthal’s career as a performer would start to decline as he went through management issues – he parted ways with both his US and UK agents within a short space of time. He took a position at Manhattan School of Music, where he would teach until his death. The pianist’s longtime pupil Dalia Sakas has penned some recollections about her mentor – a very touching tribute which I am grateful to share here:

My first exposure to Raymond Lewenthal came in a Piano Literature class (at the Manhattan School of Music) in September of 1977. I knew him only by his reputation as a recording artist and was looking forward to this class.

To the amazement of us students, the two hours of the first class were devoted to vocal bel canto, as represented by Maria Callas, who had just passed away. We heard a touching tribute to the singer while hearing about the influence of bel canto opera on the music of Chopin and Liszt. Most of the time was spent listening to Callas – and being mesmerized by Lewenthal’s grand emotions as he alternatively wept and extolled the great singer.

The following week we moved on to Piano Literature. Lewenthal knew more about the piano literature and the art of playing the piano than anyone I had ever met. I decided to change teachers – a choice that was met with quizzical stares, snide remarks, tongue-clucking, and outright laughter. I went with my gut and made the switch and worked with him until he died in 1988.

In later years I noticed a photograph of Maria Callas hanging in his home. I thought back upon that first class and wondered if he did not identify with her. They were both born in the same year (1923). She was instrumental in the revival of bel canto opera and famous in her portrayal of Norma, while Raymond had been instrumental in reviving neglected romantic piano literature, and the Réminiscences de Norma by Liszt was a work he had revived and recorded on his album The Operatic Liszt. Callas mesmerized her audiences, and one of Lewenthal’s chief concerns was that communication between artist and audience. She died alone in Paris – he was alone in New York.

He began as a teacher to me but became a thoughtful and conscientious mentor, carefully considering my repertoire choices and recital opportunities. We visited museums together and spent time with other friends.

I am forever grateful to have been accepted into his orbit and also believe that my devotion to him was accepted and valued.

In addition to the Alkan talk on WBAI featured above, Lewenthal also recorded a lecture demonstration for Columbia Records, which can be heard here:

Here is another opportunity to hear Lewenthal share his breadth and depth of knowledge of the repertoire, in a guest appearance made by Lewenthal on David Dubal’s radio program ‘For The Love Of Music’ in 1981. There is some very interesting discussion as well as performances of the highest order, primarily works of Alkan but also some Scriabin.

With his health deteriorating, Lewenthal withdrew from public appearances and moved to Hudson, New York, where he died on November 21, 1988.

To close this tribute, a live recording from late in his performing career that perfectly captures the old-school elegance and virtuosity that was the pianist’s true nature: a 1980 St Paul University account of the Strauss-Grünfeld Soirée de Vienne that showcases Lewenthal’s elegant yet big-scale playing of such delights, with sumptuous timing and nuancing, his towering fortissimi and passionate climaxes wonderfully tempered by exquisite pianissimi, as well as tonal and timing adjustments. Transcendent music-making by an extremely important pianist of the 20th century.

Comments: 3

I’ve commented on a number of YouTube posts on my admiration for and fascination with Lewenthal since the mid-’60’s, and having heard him live in 1971. There were some hero-worshipping letters (nearly cringeworthy in retrospect) to and phone conversations with him through the 70’s and early ’80’s, which he received and replied to graciously but not extensively.

His legacy will always remain a source of amazement, enjoyment and instruction to myself and musicians afterward and to come, who can catch fire from his courage to think outside of routine (music) boxes and implement his convictions with such color and persuasiveness. Happy 100th, Maestro!

Wow, how fortunate you are to have heard him live – and to have written and spoken to him. Such an incredible musician!

A wonderfully fitting tribute and homage to a great Artist! Thank you Mr Ainley.