December 15, 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the death of French pianist Monique de La Bruchollerie, who passed away in Paris at the age of 57 on December 15, 1972.

I remember very clearly when I first heard her playing: in May 1990, I was in Europe for my first ‘boots on the ground’ research trip into Dinu Lipatti and I went to spend a day with a German collector with whom I’d corresponded for a year or two, Ernst Lumpe. He is now justly celebrated for having brought Sergio Fiorentino back to the international concert circuit, and in addition to introducing me to the Italian pianist’s playing during that visit, Lumpe put a 78rpm disc on his turntable and said, “You have to hear this – you won’t believe it!” That record was Monique de La Bruchollerie’s 1947 record of the Saint-Saëns Toccata Op.111 No.6, which she played at Simon-Barere-like speed that seems absolutely impossible … and given that 78s were direct-to-disc performances, it was clear that this was exactly as she’d played it, with no editing having taken place.

Naturally, I was flabbergasted by the playing – and then Lumpe brought out her 1952 LP of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No.1, another work widely known as an opportunity for pianists to showcase their virtuosity. Here too, her fingerwork was dazzling, with rapid-fire octaves that seemed to challenge Horowitz. And, as became clear the more I listened to her over the years, there is plenty to her playing beyond the incredible force, speed, and propulsion of her account: the lyrical sections reveal astonishingly sensitive nuancing and attention to detail, and her tone lacks the brittle edge common in some more famous accounts. Here is the first movement of this superb recording:

Monique de La Bruchollerie was one of those pianists whose recordings I hadn’t come across when scouring the 2nd-hand stores in my hometown of Montreal – perhaps because her name did not figure in the two books on the topic of great pianists that I had at the time and used as reference, The Great Pianists by Harold C Schonberg and Speaking of Pianists by Abram Chasins. This being pre-internet times, one was at the mercy of what one came across in the analogue world of books, magazines, and actual records – and the recommendations of friends and colleagues. It could be too that there was less circulation of her European discs in Canada, and of course when shopping for used records one is always at the mercy of what a collector sells off and what is there on the particular day you visit the shop.

Monique de La Bruchollerie was one of those pianists whose recordings I hadn’t come across when scouring the 2nd-hand stores in my hometown of Montreal – perhaps because her name did not figure in the two books on the topic of great pianists that I had at the time and used as reference, The Great Pianists by Harold C Schonberg and Speaking of Pianists by Abram Chasins. This being pre-internet times, one was at the mercy of what one came across in the analogue world of books, magazines, and actual records – and the recommendations of friends and colleagues. It could be too that there was less circulation of her European discs in Canada, and of course when shopping for used records one is always at the mercy of what a collector sells off and what is there on the particular day you visit the shop.

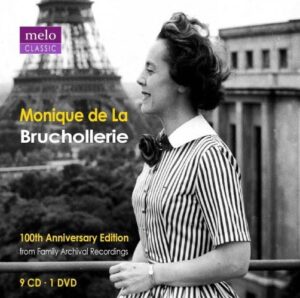

Once I moved to Japan a couple of years later (where I stayed for half of the ’90s), I was able to get transfers of some recordings from collector friends there and also obtain some of her recordings on CDs that were not issued elsewhere. About a decade later, the Canadian label DoReMi put out two double-CD sets of studio and broadcast recordings, and the following decade Meloclassic reissued a recital disc that was followed by a superb 10-disc set for the centenary of her birth: with 9 CDs largely of broadcast performances plus a DVD of a filmed Tchaikovsky Concerto performance, that highly-prized 2015 production was naturally a big hit amongst collectors (and is now regrettably but understandably sold out). Thanks to that reissue – and to YouTube making some of these and the artist’s official recordings available – Monique de La Bruchollerie is now more on the pianistic landscape of a broader cross-section of pianophiles.

A dedicated life

She was born April 20, 1915 to a family of musicians: her father’s cousin was conductor André Messager, who had premiered Pelléas et Mélisande, and as a little girl Monique met Ravel at Roland-Manuel’s villa two doors from her parents’. She entered the class of Isidor Phillip (who was also a friend of her parents) at the Paris Conservatoire when she was 7, leaving with her Premier Prix after 6 years in 1928. It should be made clear that she never studied with Cortot or von Sauer, despite such claims having been published umpteen times (this correction comes from her daughter, so hopefully the record will now be set straight).

She was born April 20, 1915 to a family of musicians: her father’s cousin was conductor André Messager, who had premiered Pelléas et Mélisande, and as a little girl Monique met Ravel at Roland-Manuel’s villa two doors from her parents’. She entered the class of Isidor Phillip (who was also a friend of her parents) at the Paris Conservatoire when she was 7, leaving with her Premier Prix after 6 years in 1928. It should be made clear that she never studied with Cortot or von Sauer, despite such claims having been published umpteen times (this correction comes from her daughter, so hopefully the record will now be set straight).

She began to perform publicly in February 1933 (her first appearance was in Belgium) and her reputation was emboldened with respectable placements in competitions: she was awarded 3rd Prize in the 1936 Vienna International Music Competition, 7th in the 1937’s III International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, and 10th at the 1938 Eugène Ysaÿe Competition (later renamed the Queen Elisabeth Competition). (You can see the laureates of the latter by clicking here: it’s worth noting that the great Arturo-Benedetti Michelangeli only placed 7th and she became close friends with the winner of that edition, Emil Gilels.)

Between 1941 and ’46, Charles Münch would help her further her career with performances of a wide range of concertos – 13 appearances in Paris, Brussels, and Rio de Janeiro – and after the war her appearances in the US began thanks to his having asked her to perform in Boston. The New York Philharmonic invited her to play three concerts a year, she gave five performances at Carnegie Hall in fifteen days, and performed with Szell, Bernstein, and Ansermet. It was in fact with the latter and not Münch that she made her North American debut with the Boston Symphony Orchestra when, on December 14, 1951 the Swiss conductor accompanied her in Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto, which they would play in New York not long afterwards.

This US debut performance was recorded (though there is a rather jarring cut at 8:18 due to missing source material) and it is indeed a vivacious account that showcases her volcanic temperament – something that Olin Downes (and later Harold C Schonberg) would state they believed required restraint, despite finding her to be “an exceptional artist” whose playing “came from the depths of the soul.”

Monique de La Bruchollerie toured Europe extensively (she gave some 400 concerts in Germany alone over the course of 20 years), with one particularly memorable event taking place in Budapest: she was the first musician to open the post-Revolution season in January 1957 and she was greeted by some 20 minutes of rapturous applause. She was subsequently interrogated by the military police, asking if she supported the Revolution or not, to which she replied, “I defend music!” Alas, her having played in Communist countries meant she would no longer be invited back to the United States: the CIA suggested she make the choice and she was not one to be told what to do. Other consequences of playing in politically volatile locations included scores being examined in case her fingerings were coded messages (they were apparently stolen for this reason in Johannesburg in 1960, requiring new ones to be shipped through diplomatic channels) and rehearsals behind the Iron Curtain being sacrificed because she was held in freezing airport hangers for questioning for hours at a time. Her interest was in bringing music to the people of these oppressed countries and not to cower to the political machinations of any regime.

Monique de La Bruchollerie toured Europe extensively (she gave some 400 concerts in Germany alone over the course of 20 years), with one particularly memorable event taking place in Budapest: she was the first musician to open the post-Revolution season in January 1957 and she was greeted by some 20 minutes of rapturous applause. She was subsequently interrogated by the military police, asking if she supported the Revolution or not, to which she replied, “I defend music!” Alas, her having played in Communist countries meant she would no longer be invited back to the United States: the CIA suggested she make the choice and she was not one to be told what to do. Other consequences of playing in politically volatile locations included scores being examined in case her fingerings were coded messages (they were apparently stolen for this reason in Johannesburg in 1960, requiring new ones to be shipped through diplomatic channels) and rehearsals behind the Iron Curtain being sacrificed because she was held in freezing airport hangers for questioning for hours at a time. Her interest was in bringing music to the people of these oppressed countries and not to cower to the political machinations of any regime.

Her performing career of 33 years came to an end when, after a December 18, 1966 recital in Cluj, Romania, the 51-year-old pianist was in a serious car accident that resulted in a fractured skull, the loss of an eye, and sufficient irreversible injury to her hand to prevent her from playing professionally again. Having already begun teaching at the Paris Conservatoire after the death of her mother in 1959, she renewed her focus on her students, her most famous being Cyprien Katsaris and Jean-Marc Savelli. Sadly, she died in Paris just a few days before the 6th anniversary of the Romanian accident. She was 57 years old.

Recorded legacy

Monique de La Bruchollerie’s discography consists of a handful for HMV 78s in the late 1940s (a 1943 Beethoven 4th Concerto with Cluytens was unissued at the time), another 78 of Scarlatti for the Nixa label in 1950, and a scant number of of LPs: a few the 1950s for Vox (also issued on Ariola, Pantheon, and Opera) and a couple more in the 1960s for Eurodisc. Today the vast majority of her available recordings are broadcast performances, issued on a variety labels and accessible online.

The opening selection in Meloclassic’s centenary tribute was the unpublished May 14, 1943 HMV account of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G Major Op.58 with André Cluytens conducting the Orchestre De La Société Des Concerts Du Conservatoire, the pianist’s first recording. Aged 28 at the time, she plays with astonishing musical maturity, using her prodigious technical mastery to serve the music with exquisitely refined tonal colours and dynamic shadings (her pianissimo trills are truly breathtaking), navigating the fine balance between the more probing and joyful flavours of the work – a truly eloquent rendition. She plays the Saint-Saëns cadenzas in the first and third movements.

Among her October 22, 1947 HMV recordings (that legendary Toccata above was recorded the same day) is the Haydn Sonata in E Minor Hob XVI:34, an account that reveals that she was not just a powerful and emotional performer but a sensitive one quite capable of restraint and charm: what deft articulation, sensitive use of pedal, refined dynamic control, and rhythmic precision.

At the same session as this Haydn she set down a towering account of Chopin’s Ballade No.4 in F Minor Op.52, grandly phrased (what a left hand!) with sensitive ebb and flow, never bombastic in the most heroic moments but certainly with incredible momentum and passion.

Among her Vox recordings is this 1956 account of Franck’s Variations symphoniques with the Orchestre De L’Association Des Concerts Colonne conducted by Jonel Perlea. She plays here with wonderful rhythmic buoyancy, lovely fluid phrasing, marvellous timing, refined dynamic layering, and mindful use of articulation.

While she is most known for her accounts of the Romantic repertoire, we have already seen that Madame de La Bruchollerie excelled in earlier music with the Haydn example above, and her studio accounts of two Mozart Concertos are magnificent as well. The Piano Concerto No.20 in D Minor K.466 captures the simultaneous depth and innocence of Mozart’s idiom with a combination of directness and sensitive nuancing. What marvellous highlighting with the left hand, sumptuous dynamic shading, and mastery of the pedal in lyrical passages.

Here are some wonderful concert recordings of her playing Chopin that were recorded by French radio in 1959 and 1962. Throughout these performances, she plays with beautiful tone (even if the pianos are not all up to standard), clear textures, fluid phrasing, and truly elegant timing.

Here is film footage of the pianist playing the final movement of Chopin’s Sonata No.3 in B Minor Op.58 on the ORTF program Moi j’aime on June 14, 1965. As usual, we hear a sense of momentum and drive tempered by fluid contours of expressive phrasing.

A little more film footage: an excerpt from the DVD in the Meloclassic edition in which we see her playing part of the 1st movement cadenza of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No.1 in a French television broadcast of February 16, 1963 – a truly heartfelt account with sumptuous phrasing in the lyrical passages masterfully contrasted by her deft articulation and thrilling octaves, all without losing a sense of line … and what emotive timing:

Another of the pianist’s signature works was the Saint-Saens Piano Concerto No.5 in F Major Op.103 (the last movement of which is the work on which the Toccata is based), and this April 16, 1965 broadcast captures her playing at its dynamic peak. About 18 months prior to her career-ending accident, Madame de La Bruchollerie is in exceptional form (even if the orchestra is occasionally not on track), playing with her trademark fusion of elegant refinement and dazzling dexterity – and very well served by the piano and recorded sound.

This moving television footage features a TV interview in which the artist (whose name is misspelled on the screen!) recounts some details of the accident in Romania and its aftermath. She states that she had played three times that day: at 10am for students and then recitals at 4pm and 8pm – two public performances so that more music lovers could attend. When she was told there was no flight, she asked to be driven but there was a collision on the snowy road. She remembered nothing of the actual crash as she went into a coma immediately and lost a lot of blood (she was the only one injured), but by great serendipity a Red Cross vehicle was driving by so help was fortuitously right there. She says that she now needed daily to greet the day with the reality that she cannot play but that with a physical compromise, spirit grows stronger, and it is inherently stronger than the body.

As a final offering, the last work that she played in public at her last December 18, 1966 recital in Cluj: her final encore, a performance of Debussy’s Prélude La cathédrale engloutie. Although she is not well served by a poorly tuned piano and the recorded sound (the tape fades in gradually and out quite suddenly), we can still appreciate Madame de La Bruchollerie’s transparent textures, broad dynamic range, mastery of the pedal, and the magical atmosphere she creates – an artist who was fully absorbed in her creative expression and who draws the listener into her world.

Many thanks to Frédéric Gaussin for his invaluable assistance in my preparation of this tribute

One comment

Recently heard the St.Saens Etude. Dazz-l-ing!