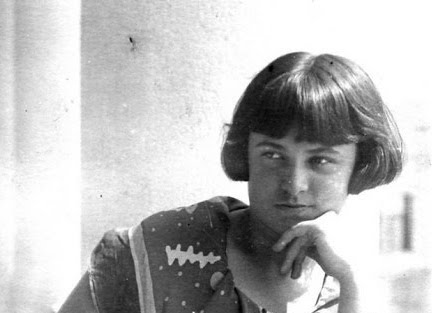

Having only just realized that today is the 70th anniversary of the death of Rosa Tamarkina, I am quickly preparing this commemorative post with some representative recordings and basic biographical information that will then be expanded into a tribute more worthy of such a supreme artist.

Tamarkina’s death of cancer at the age of 30 on August 5, 1950 – four months before Dinu Lipatti’s untimely passing – was a tragic loss to the musical world. At a young age, her talent was abundantly clear, as evidenced by some very early recordings of the artist: here she is playing Liszt’s Rigoletto Paraphrase and Hungarian Rhapsody No.10 in 1935, at the age of 15.

A pupil of the great Alexander Goldenweiser who would later work with Konstantin Igumnov, Tamarkina was already played publicly in her early teens. In 1937 she participated in the 3rd International Chopin Competition in Warsaw, where at the age of 16 she was awarded second prize (her compatriot Yakov Zak came in first). Neuhaus wrote about that occasion that “Rosa Tamarkina made a real sensation on the competition – not merely because of her age. Despite her young age, she is beyond doubt a perfectly matured, perfectly conscious pianist. Backhaus shouted to me: ‘This is marvelous!'”

Some film footage shortly after that competition was made when she was back home in Russia: here we see her playing Chopin’s ‘Black Key’ Etude with a combination of refinement and inspired virtuosity. You can see you can see Yakov Zak, Nina Yemelyanova, and Heinrich Neuhaus sitting behind her in the opening sequence. What bold yet poetic playing, with sparkling and full-bodied tone, clear fingerwork, and attentive voicing.

Here she is again shortly after that win, aged 17, in Goldenweiser’s classroom, playing a Chopin Mazurka with a soaring line, wonderful dynamic shadings (appreciable despite the poor sound), and marvellous rhythm:

Tamarkina had a performing career that was very successful but later limited by both her teaching at the Moscow Conservatory and illness. She was diagnosed with cancer at the age of 26 and with treatment was able to survive a few more years, the period from which the bulk of her recordings (both commercial and concert) derive. Her playing was notable for its combination of power and sensitivity, with grandly-shaped phrasing that was never angular, strength that never crossed the edge into aggression, her tone deep and powerful yet never harsh or aggressive.

Tamarkina’s success at the Chopin Competition has led to her name being inextricably linked with that composer, and she was indeed a sensitive yet bold interpreter of his music. Chopin’s Polonaise-Fantaisie is an ideal vehicle for her beautiful blend of sensitive lyricism and bold declamatory style, with rhythmic propulsion that isn’t overly driven, and featuring dramatic emphasis without any loss of tonal integrity (despite a substandard piano), her subtle pedalling never compromising clarity of texture:

She was equally at home with other Romantic composers, and several recordings of works by Schumann and Liszt demonstrate her fine pianistic and musical attributes. This 1948 reading of Schumann 3 Phantasiestücke Op.111, despite its rather restrictive sonic framework, showcases her rhythmic momentum, wonderful voicing, lyrical legato phrasing, and natural timing.

Of course Tamarkina was at home in the music of her native Russia, her few recordings of Rachmaninoff being exemplary. This 1948 concert performance of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto is a grand reading that demonstrates her robust sonority, beautifully shaped lines, rhythmic certainty, and wonderful balance between hands.

Had Tamarkina not died so tragically young, she surely would have enjoyed an international career that would have seen her recognized as one of the supreme pianists hailing from her country. She and Emil Gilels had been married from 1940 to 44, and when one considers the reach of Gilels’ decades-long career, it is almost painful to imagine how rapturously she might have been received by international audiences in concerts and recordings for major labels – alas, it was not to be. For now, we have just a handful of precious recordings and snippets of film that are all in need of skillful restoration. But what timeless and inspired music-making we can appreciate of what remains – and the gratitude we should feel that we have what we do.

Comments: 2

Thank you from my heart!

Thank you so much for these sparkling gems.