We are fortunate and privileged to be able to hear the playing of many esteemed musicians born and trained in the 19th century, including some who chose not to record officially. It can be hard for us today to imagine that preserving one’s playing for future generations was not on the mind of every performing artist and yet that was the case for many; but fortunately there are many instances where concert, broadcast, or test recordings have been conserved, allowing us to hear some musicians whose artistry might have otherwise disappeared into thin air.

We are fortunate and privileged to be able to hear the playing of many esteemed musicians born and trained in the 19th century, including some who chose not to record officially. It can be hard for us today to imagine that preserving one’s playing for future generations was not on the mind of every performing artist and yet that was the case for many; but fortunately there are many instances where concert, broadcast, or test recordings have been conserved, allowing us to hear some musicians whose artistry might have otherwise disappeared into thin air.

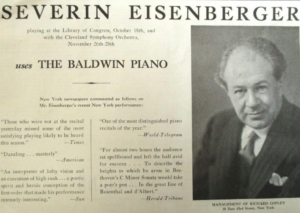

We should certainly be grateful that despite the Polish pianist Severin Eisenberger’s lack of interest in the medium, some recordings have survived, and through a most remarkable circumstance. Here is what Allan Evans, the late musical archeologist (as he aptly described himself) responsible for locating and releasing some of these performances, said about how these performances be preserved:

“After [Eisenberger’s] passing in 1945, his widow received a mysterious box by the custodian of their Manhattan apartment house: the pianist once intended to throw it away. He told the custodian that it contained records made of his radio recitals and that he was displeased with the mistakes. The custodian realized his mistake and kept the box, returning it to his widow after the pianist’s death. For a major pianist who never recorded, the box contained more than a mere idea of his art.”

It is truly fortuitous that these precious Eisenberger broadcasts were not destroyed as the pianist had hoped (that custodian lived up to the essence his profession!), as the music-making they reveal is truly stupendous. In all the performances that have been released (and quite a bit else has not yet been made available), we can hear Eisenberger playing with an incredibly deep but beautiful ringing sound, phrasing that naturally rises and falls as if the music were words spoken by a skilled actor, exquisite clarity of articulation and rhythmic pulse, and pedalling that never obscures the clarity of texture and the line (in other words, his playing is superb). Even if the qualities of his playing weren’t enough on their own, the lineage in which Eisenberger was trained and musicians with whom he had contact makes his artistry of particular interest.

Born July 25, 1879, Severin (Seweryn) Eisenberger studied in his native Poland with Flora Grzywińska (who had also taught Ignaz Friedman) before honing his craft with two pupils of Czerny, the legendary Theodor Leschetizky and the less remembered Heinrich Ehrlich. Both had been among Czerny’s favoured pupils, and given that Czerny had studied with no less than Beethoven himself, Eisenberger was surely able to receive some remarkable insight from these teachers. He additionally heard Beethoven performances by some of the most esteemed interpreters of his time – Liszt pupils Hans von Bülow and Eugen D’Albert, as well as Anton Rubinstein (for whom he also played) – and he also heard Brahms himself. Of the latter he wrote,

“The impression of Brahms never left me. I was at an impressionable age anyhow and Brahms was the idol of the hour among the younger musicians. I did not pretend to understand him, at least, not all of him, but I was a deep student of his compositions. The more I worked at them, the more I understood. He was my hero, and to hear and see him was an encouragement that sent me to greater enthusiasm. Many years later, when I was at the home of Miller-Aichholz in Vienna, I heard him play again. I shook his hand tremblingly, because he seemed to me a musical god. I played both the B-flat and D minor piano concertos in more cities of Europe than I can remember.”

Eisenberger taught extensively, at the Vienna and Kraków conservatories (the latter from 1914 to 1922) – one wonders whether the New York Times obituary of the pianist was accurate when it stated that he had been head of the piano department of the Moscow Conservatory (it seems unlikely) – and he was highly respected both as a performer and a teacher. Like so many artists of his generation he left Europe to move to the US, settling in Cleveland in 1928, where he taught before taking a position at the Cincinnati Conservatory.

Eisenberger taught extensively, at the Vienna and Kraków conservatories (the latter from 1914 to 1922) – one wonders whether the New York Times obituary of the pianist was accurate when it stated that he had been head of the piano department of the Moscow Conservatory (it seems unlikely) – and he was highly respected both as a performer and a teacher. Like so many artists of his generation he left Europe to move to the US, settling in Cleveland in 1928, where he taught before taking a position at the Cincinnati Conservatory.

He appeared throughout the US to great reviews – the New York Times was continually effusive in their praise – and from 1933 he appeared in New York under the management of Richard Copley, who also represented Josef Hofmann, Benno Moiseiwitsch, and Harriet Cohen. During his time in the States, he played cycles of the complete Beethoven 32 Piano Sonatas and apparently gave the Cleveland Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 K.491 (as late as 1931). He often gave Saturday afternoon WABC radio broadcasts at the Cincinnati Conservatory in the 1930s, where his pupil Vivien Harvey Slater (who recorded a good deal of Czerny) turned pages for him, sessions from which some of the existing recordings shared here derive. He died in New York on December 11, 1945.

Prior to the death of Allan Evans a couple of years ago, the producer had included in some compilation CDs a handful of solo recordings and two concertos played by Eisenberger, and he also provided a solo Beethoven Sonata recording for release elsewhere – details and most of the recordings themselves can be found below. Fortunately quite a bit more does exist (including several complete concerti) and these are safely preserved by the late Evans’ family, and one certainly hopes that they will soon be made available.

The solo recordings in this first clip give us an opportunity to appreciate Eisenberg’s truly remarkable tone, which has a particularly ‘centred’ quality – I don’t know how else to describe this quality of vibrancy, clarity, and purity; at all dynamic levels, his sonority has an inner strength and focus, yet without any hardness or ‘edge.’ Throughout these fantastic readings, that directness of tone rings through, along with his beautifully forged melodic phrasing, transparent textures, subtle dynamic shading, and wonderful timing. All of these performances are superb, with the Brahms being particularly mesmerizing (not a surprise, given the pianist’s having heard him and admired him so greatly).

0:00 Kodaly Hét zongoradarab: No. 2 Székely keserves (May 1, 1937)

2:32 Kodaly Hét zongoradarab: No. 6 Székely nóta (May 1, 1937)

5:57 Brahms Intermezzo op. 76 No. 3 (March 4, 1939)

8:44 Brahms Rhapsody op. 79 No. 2 (March 4, 1939)

13:49 Schubert-Liszt Soirée de Vienne No. 6 (February 13, 1937)

19:51 Brahms-Friedman Waltz No. 15 (March 4, 1939)

21:15 Brahms-Friedman Waltz No. 2 (March 4, 1939)

23:04 Schumann Fantasiestücke op. 12 Des Abends (October 23, 1937)

25:59 Schumann Fantasiestücke op. 12 Aufschwung (October 23, 1937)

29:19 Schumann Fantasiestücke op. 111 No. 2 (March 4, 1939)

34:09 Schumann Novellette op. 99 in B minor (March 4, 1939)

37:23 Scarlatti-Tausig Capriccio in E (March 4, 1939)

The Sakuraphon label included in its Pupils of Leschetizky series a fascinating Beethoven Moonlight Sonata not previously issued by Evans, and I shared the first movement in a podcast devoted to “Unsung Pianists” (the third in my series devoted to overlooked pianist). This is the first performance that I featured in the episode and is well worth hearing:

Among the two concerto recordings of Eisenberger that Evans made public – both with the Cincinnati Conservatory Orchestra under Alexander von Kreisler – is a March 4, 1938 account of the Grieg Concerto. This should be of particular interest since the pianist had some decades prior to this concert played the work in Berlin with the composer on the podium. Here too we can clearly hear that gorgeous tonal palette, transparency of texture, and magnificent phrasing that characterize Eisenberger’s playing.

Finally, we have a superb May 14, 1938 concert performance of Chopin’s F Minor Concerto, which makes use of a different orchestration than the norm. Eisenberger plays with his exquisitely refined sonority, soaring phrasing, expressive (but never exaggerated) timing, and skillful pedalling that never obscures the clarity of texture and the line – a truly noble and refined interpretation.

A letter dated January 16, 1945 (just under a year before he died at age 66) shared online by Allan Evans shows a shift in pianism that Eisenberg noted was starting to take root. Referring to some pianists that he had just heard at Town Hall in New York, he wrote, “They all play very fast and loud. The result is that maybe the next day somebody plays still faster and louder. If this is all what music represents, then I give up. The critics seem to wait for someone who is able to make nice music and is also a good technician.”

At a time when faster and louder often seems the name of the game, Eisenberger’s pianism, with its skillfully crafted phrasing and depth of beautiful tone serving his intelligent and heartfelt conceptions, is a balm for the soul. A 1930 New York Times review referred to his playing “with the mellowness of a mature artist,” noting his recitals were “an opportunity to hear great music interpreted by a sensitive and sincere artist… Many virtuosi, many styles, and Mr Eisenberger is for the musician.” Long may he be remembered and admired to the degree that his majestic music-making merits.

Comments: 2

Hearing just the intriguing Kodaly pieces, the Soiree de Vienne, and others I’m sold. Another Golden Age worthy stuck in the boondocks of pianistic history too long. If Eisenbeger himself intended to discard these performances, he must have had stratospheric standards for himself (not to mention any pupils!). That beautiful, eloquent tone in everything. Much thanks for bringing him to the fore like this!

So glad you ‘get’ him … truly, that tone IS everything – as is everything else! Indeed, one wonders what would have satisfied him if these recordings were what he wanted to discard. Truly an impeccable pianist, one to be revered alongside the other greats of his time!