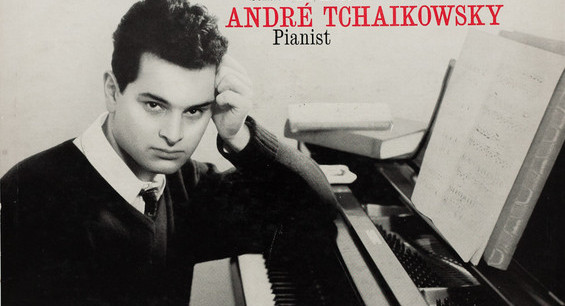

The music world has known many very individual artists, whose strong personalities and unique character informed their playing. One such pianist was the regrettably short-lived Polish-born pianist André Tchaikowsky, whose early death at the age of 46 was a serious loss for the musical world, and whose posthumous wishes were as unique and headline-grabbing as his artistry.

The Polish musician was not born with the surname of the famed Russian composer by which he would later be recognized. Born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer in Warsaw on November 1, 1935, the pianist would go through a name change as a young boy when his grandmother attempted to hide his Jewish origins by forging documents such that he would become Andrzej Czajkowski. It was successful for the young boy’s survival (although he and his grandmother were rounded up in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 and sent to the Pruszków transit camp, they were released in 1945) – however, his mother would die in Treblinka. While his official bio would state that his father had died, this was not true: his father had, in a sense, died to him when he later disowned his son for wanting to be a musician instead of a doctor or lawyer, leading them to cut all ties.

Czajkowski studied piano at the Lodz State School under Wanda Landowska’s former pupil Emma Altberg before going to Paris to study with the great pedagogue and pianist Lazare-Lévy. He returned to Poland in 1950, studying with Olga Iliwicka-Dąbrowska at the State Music Academy in Sopot and with Stanisław Szpinalski at the State Music Academy in Warsaw. When he placed eighth in the fifth International Chopin Competition in 1955, he went to study with renowned Chopin specialist Stefan Askenase and then won the third prize in the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Belgium the following year.

This upload of a recording from the 1955 Chopin Competition prize winners’ concert, a reading of Chopin’s Polonaise-Fantaisie Op.61 that features lovely tone and attentive phrasing, albeit without the full boldness of touch and tensile strength of phrasing that would become characteristic of his later playing:

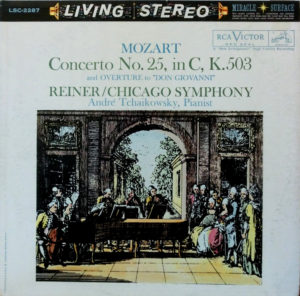

Czajkowski would change the spelling of his last name to the more familiar Tchaikowsky and in 1957 got a recording contract with RCA, for whom he would record a series of discs totalling a mere three hours, now finally rereleased in a complete box set for the first time. Unfortunately the Ravel Gaspard de la nuit from his debut disc is pitched sharp on both the LP and the latest CD transfer (it’s unclear if the piano was sharp or if the tape simply ran at the wrong speed). Over the course of 3 years he produced a mere 4 LPs, with a significant amount of material remaining unreleased (and apparently still considered unfit for release when the CD set was put out early in 2018). Fortunately the released performances are of the highest standard, with stunningly refined musicianship throughout.

One anecdote surrounding his recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.25 with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony on February 15, 1958 is rather amusing. While in rehearsal for the recording, Tchaikowsky made the offhand comment that he had never performed the work in public before, which sent Reiner into a fit of anger: “How dare you record a work with me that you haven’t played!” It clearly didn’t matter that Tchaikowsky was playing brilliantly (or that he could learn a work and play it to perfection instantly) – Reiner was furious and there were fears that the session would be canceled.

One anecdote surrounding his recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.25 with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony on February 15, 1958 is rather amusing. While in rehearsal for the recording, Tchaikowsky made the offhand comment that he had never performed the work in public before, which sent Reiner into a fit of anger: “How dare you record a work with me that you haven’t played!” It clearly didn’t matter that Tchaikowsky was playing brilliantly (or that he could learn a work and play it to perfection instantly) – Reiner was furious and there were fears that the session would be canceled.

Fortunately, it was not and they recorded not only that Mozart Concerto but also the Bach Concerto in F Minor BWV 1056 (on the same day), and Tchaikovsky would return within a few years to play Prokofiev’s Concerto No.2 in Chicago under Reiner’s baton (if only a broadcast recording could be found!).

Here is the recording of the Bach Concerto, showcasing his deft articulation, spritely sense of rhythm, and transparency of texture.

One of his handful of records for the RCA label is this disc of works by Chopin recorded in March 1959 which showcases his beautifully polished tone, elegantly forged phrasing, refined dynamic shadings, with some bold gestures, creative voicing, and effective rubato, forging interpretations that exude drama, charm, depth, and magnetism.

Tchaikowsky’s quirky character would make things challenging for his career. Arthur Rubinstein was a huge supporter and would arrange for Tchaikowsky to be represented by his manager, the legendary Sol Hurok – but Tchaikowsky would find it stifling to be under the wing of such a famous pianist and his management, so he soon left and moved to Europe. There too he would consistently demonstrate erratic behaviour that didn’t particularly endear him to everyone, although those who recognized his genius would tolerate some of his eccentricities.

On one occasion when still based in the US, he stated that he would not play his upcoming concert in Boston unless someone came to tuck him into his hotel bed (this is not a euphemism for anything less innocent than it sounds – that was literally all he wanted). Hurok’s office did indeed get someone on a train to go to his hotel to do that. (When one considers that he lost his mother so young and was living the career that led to a separation from his father, his request is in fact rather sad and moving.)

On a later occasion in London in the early 1970s, a manager’s assistant found Tchaikowsky about to leave the hall at which he was scheduled to give a BBC broadcast ten minutes before the start time. She thought he was heading out for a cigarette, but when she approached him, he smiled rather innocently while saying sort of sweetly, “I’m going home. I can’t play this concert.” The assistant and André’s secretary were busily wringing their handkerchiefs to shreds while trying to talk some sense into him, and while the assistant can no longer remember what she said to convince him to stay and play, she was successful. Such eccentricity was borne out of a deep-seated desire to do his best, which led him to want to play fewer concerts than management sometimes desired: he got into a rather sharply-worded disagreement with his London manager, who wanted him to play more concerts, but Tchaikowsky would not budge on the numbers.

On a later occasion in London in the early 1970s, a manager’s assistant found Tchaikowsky about to leave the hall at which he was scheduled to give a BBC broadcast ten minutes before the start time. She thought he was heading out for a cigarette, but when she approached him, he smiled rather innocently while saying sort of sweetly, “I’m going home. I can’t play this concert.” The assistant and André’s secretary were busily wringing their handkerchiefs to shreds while trying to talk some sense into him, and while the assistant can no longer remember what she said to convince him to stay and play, she was successful. Such eccentricity was borne out of a deep-seated desire to do his best, which led him to want to play fewer concerts than management sometimes desired: he got into a rather sharply-worded disagreement with his London manager, who wanted him to play more concerts, but Tchaikowsky would not budge on the numbers.

He was always concerned about the validity of his interpretations, and his April 23, 1972 Queen Elizabeth Hall concert reveals to what extent. He had programmed Bartok’s Out of Doors Suite and told his friend and colleague Radu Lupu, who planned to attend the recital, that the concert started 30 minutes later than it actually did because he knew that Lupu was familiar with the work and didn’t want him to be present when he played it (it was the first piece on the program). He also asked for the house lights to be dimmed lower than usual so that no one would be able to follow with a score had they brought one with them. Below is an upload of that performance (audio courtesy of the andretchaikowsky.com website), one of only two extant recordings of the pianist playing Bartok – despite his concerns, Tchaikowsky played with tremendous musicality and authority, demonstrating the clarity of texture, rhythmic vitality, mindful shaping of phrases, intelligent balance of voices, and rich array of tonal colours that made his playing so distinctive. Even with the massive fortissimo of the opening, his playing is not tonally harsh.

One of the signs of a great performer is being able to make one hear familiar music as if for the first time without distorting it by doing something ‘new’ or ‘different’ just for the sake of it. Tchaikowsky’s 1974 reading of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini – a work he didn’t record commercially (in fact, he recorded not a single work by the composer) – is a performance that points to this capacity. The playing throughout the work is superb, but it is particularly that famous 18th variation that is thoroughly remarkable: usually the pianist plays the variation softly and tenderly before the orchestra comes in with more passion and at a louder volume – but Tchaikowsky had the orchestra sustain the lower dynamics with a gentler treatment of the beautiful melody, which is absolutely mesmerizing and musically very effective. (It was not just on this occasion that he did this – a broadcast recording from two years earlier features the same treatment of this variation.) That variation begins at 15:07 below, with the orchestra entering at 16:08 (though of course the entire performance should be heard).

At the same concert as the Rachmaninoff Rhapsody, he played the Ravel Concerto for Left Hand, another work he had not recorded commercially (his first commercial LP featured Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit), and his refinement and precision were ideally suited to the composer’s music. This performance too features staggering musicianship, revealing Tchaikowsky’s tremendous power at the keyboard and the depth of his musical mind, with wonderfully spacious phrasing, beautifully forged lines, and magnificent tonal and dynamic nuancing. Apparently the pianist stated that his greatest challenge with the work was knowing what to do with his right hand and on at least one occasion wore a sling for his right arm!

Tchaikowsky had a broad repertoire yet unfortunately recorded very little for posterity. In addition to his four discs for RCA in the late 1950s, he recorded a series of records for Columbia in Europe in the 1960s, several of which would remain unreleased. He did not record any Beethoven, however, despite the depth that his burnished yet powerful sound, shaping of his phrasing, and clarity of textures could bring to the composer’s music. This October 12, 1976 broadcast recording of the Sonata No.31 in A-Flat Major Op.110 is remarkable for its exquisite singing tone, soaring yet fluid phrasing, and the magnificent interplay between lines in the left and right hands, along with the brilliant manner in which he highlights primary and secondary subjects. To think that if it were not for an existing radio broadcast and the internet, this recording would likely be lost!

Tchaikowsky would sadly leave us at too young an age: on June 26, 1982 he succumbed to stomach cancer at the age of 46. In death he was as eccentric as in life: he requested that his skull be bequeathed to the Royal Shakespeare Society for use on stage in their productions. Indeed, he finally did take on his role as the late Yorrick in a production of Hamlet (with David Tennant in the title role) but the controversy around the use of a real skull led to its no longer being used.

Fortunately, the pianist’s musicality is still centre stage for music lovers: his complete RCA discography is available for the first time in a complete set, and a selection of wonderful broadcast performances is available on a superb disc on the great Meloclassic label, and he was the subject of a 2015 documentary (which I have regrettably not yet been able to see) – it is certainly to be hoped that more performances by this great artist will become available. Those wishing to explore more of this great pianist should investigate the superb memorial website andretchaikowsky.com, which is a model website for its comprehensive presentation of the pianist’s life and art, with every available extant recording being available for streaming (the broadcast recordings presented here derive from their sources), along with concert programs and other memorabilia – deep gratitude to those who are so admirably preserving his memory.

Many thanks to Laura Miner for sharing her recollections of Tchaikowsky from her time working with him in the 1970s.

Below is a broadcast of The Music Treasury from June 17, 2018, in which the host Gary Lemco and I present a number of commercial and broadcast recordings of a wide range of repertoire from Bach to Prokofiev (including a couple of the performances linked in this blog post).