One of the marvels of our technological age is the possibility of new discoveries in musical arenas. Old records are being reissued and made more available than at any other time in history and archival recordings from radio broadcasts that have never been previously released can now be streamed or purchased, an exciting proposition for music lovers interested in the performers of the past. ‘New’ names are becoming known to present-day listeners as artists whose recordings were once only available overseas or unissued for decades become available. But even in such a climate it is unusual to come across an artist who died as late as 1970 who had a brilliant career yet didn’t make a single commercial recording – and whose current discography is made up entirely of taped practice sessions from the twilight of his career.

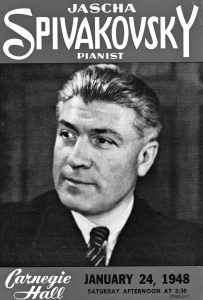

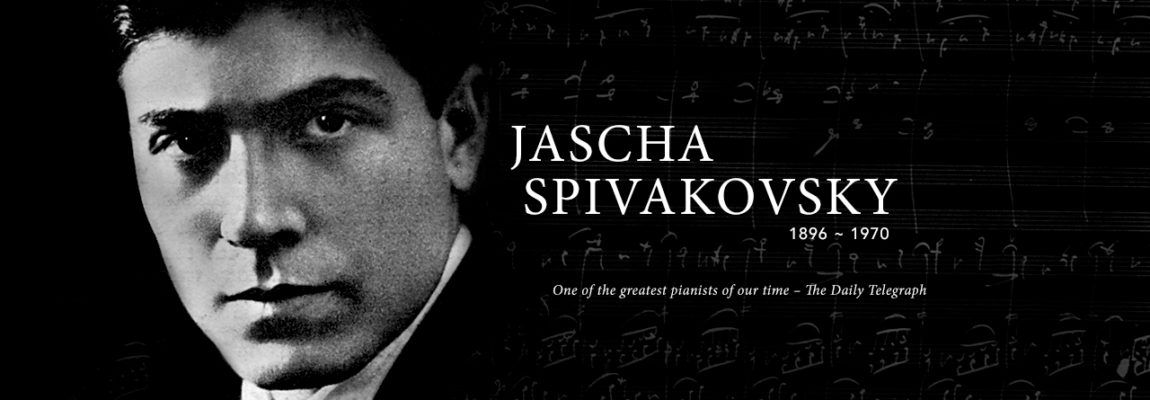

Aficionados of historical classical recordings will be familiar with the name of the violinist Tossy Spivakovsky, but even the most ardent collectors would likely not know that his brother Jascha was a highly esteemed pianist who had a luminous international career. Jascha Spivakovsky studied with Moritz Mayer-Mahr, a pupil of both Liszt and Anton Rubinstein, which in and of itself might not have guaranteed his skill as a performer; but with his highly honed technique and brilliant intellect, Spivakovsky had a degree of pianistic prowess limited to very few a generation and he gained international renown in a career that spanned six decades. Critics were adulatory in the extreme, Neville Cardus having written to the pianist personally to praise his Beethoven Op.111 while others regularly compared the performer to the most legendary pianists that came before him (the fiery Carreño was one frequently mentioned in his early years and at his Leipzig debut in 1910 he was declared to be ‘the heir to [Anton] Rubinstein’).

Aficionados of historical classical recordings will be familiar with the name of the violinist Tossy Spivakovsky, but even the most ardent collectors would likely not know that his brother Jascha was a highly esteemed pianist who had a luminous international career. Jascha Spivakovsky studied with Moritz Mayer-Mahr, a pupil of both Liszt and Anton Rubinstein, which in and of itself might not have guaranteed his skill as a performer; but with his highly honed technique and brilliant intellect, Spivakovsky had a degree of pianistic prowess limited to very few a generation and he gained international renown in a career that spanned six decades. Critics were adulatory in the extreme, Neville Cardus having written to the pianist personally to praise his Beethoven Op.111 while others regularly compared the performer to the most legendary pianists that came before him (the fiery Carreño was one frequently mentioned in his early years and at his Leipzig debut in 1910 he was declared to be ‘the heir to [Anton] Rubinstein’).

Jascha Spivakovsky toured the globe and played under major conductors equally effusive in their praise – Strauss, Furtwängler, Monteux, Goosens, Barbirolli, Boult – yet he never made a recording as piano soloist. The reasons are rather complex: he did go to the Parlophone studios to accompany Tossy and apparently made some test solo recordings for them, but these were likely acoustical recordings and he was unhappy  with the sound. He moved to Australia in 1933 to escape the Nazis (Richard Strauss had warned him to leave as Jascha’s name was on a hit list – he jotted the musical notation to the William Tell Overture in a letter, a hint that he should get out ASAP) and put his career on hold until the end of World War 2 to help others escape Germany.

with the sound. He moved to Australia in 1933 to escape the Nazis (Richard Strauss had warned him to leave as Jascha’s name was on a hit list – he jotted the musical notation to the William Tell Overture in a letter, a hint that he should get out ASAP) and put his career on hold until the end of World War 2 to help others escape Germany.

Although Spivakovsky toured until 1960 in locations where recordings were regularly made by other artists also not living in those centres – such as London and New York – he was not approached by any companies until 1959, when a flawless broadcast of his Emperor Concerto attracted some producers’ attention. Jascha had not himself sought out the opportunity to make recordings, in post-war years needing to re-establish his reputation on the concert platform and in any case preferring to perform live. But with a health scare in 1960 putting an end to his international touring, he ended up dying in 1970 without making a single solo recording.

Fortunately for posterity, Jascha’s son Michael recorded the pianist in practice sessions at their Melbourne home (sometimes without the pianist knowing), in a musical salon that had welcomed the greatest musicians visiting Australia – Moiseiwitsch, Schnabel, Kapell, Cherkassky, Rubinstein, Arrau, and even Victor Borge would all visit when Down Under (indeed, the ill-fated Kapell spent the last night of his life there, staying up all night as Jascha and Kapell played for each other, before boarding the plane whose crash ended his life at the age of 31… eerily, Kapell showed the young Michael the short lifeline on his hand, saying ‘I shouldn’t be here…’). Decades later, technology has finally enabled the poor-quality tapes to be remastered to a degree sufficient for allow their release.

The family was justly concerned that releasing private tapes made for the pianist’s personal use might be of limited appeal and not do him justice. Fortunately, Spivakovsky’s playing is of such incredibly refined and potent musicality that it is almost inconceivable to the listener that the performances are one-take practice readings. Indeed, I was recently playing the first movement of the Waldstein for a colleague who marvelled, as had I on my first listen (and on several hearings since), at the incredibly brisk tempo of the first movement in which the voicing is uncannily clear and consistent; he stated, ‘Not that this is the most important thing – but even with everything else he’s doing, he hasn’t dropped a single note.’ Even more remarkable: the performance was recorded when the pianist was 70. There is absolutely nothing in the playing that could lead one to surmise that the performer was anywhere near an age when faculties might decline. Listen for yourself:

Andrew Rose of Pristine Classical has done an exceptional job in remastering the recordings and has produced two CDs in a series that will include several more. The title ‘Bach to Bloch’ applies to the entire planned collection of discs, which will contain repertoire that spans a wide range of repertoire from Bach through classical and Romantic composers to more modern composers such as Debussy, Kabalevsky, and Bloch (a concert recording of whose Concerto Symphonique will close out the final volume). The first two  discs feature solo repertoire arranged in chronological order in a traditional recital format and reveal the pianist’s affinity to a wide array of styles. Yet while always playing idiomatically for each composer, there are qualities in Spivakovsky’s pianism that are consistently noticeable: an incredibly refined sonority (even when the piano is out of tune, as it regrettably is in one case); phrasing that is masterfully shaped by fusing dynamics, tonal colour, and timing; a rubato that breathes and defies bar lines but serves the architectural structure of the music without the rhythmic pulse ever being lost; voicing that is consistent to the highest degree (the only pianist I’ve heard able to voice with such exquisite and consistent clarity is Lipatti); unbelievably subtle and mastery of the pedal; and incredible digital dexterity (though he apparently had such thick fingers that he had to rely on unorthodox fingerings – as will be revealed when a filmed performance is eventually issued). He is, quite simply, one of the greatest pianists I have ever heard – quite rightly dubbed by Rose as ‘the greatest pianist you’ve never heard of.’

discs feature solo repertoire arranged in chronological order in a traditional recital format and reveal the pianist’s affinity to a wide array of styles. Yet while always playing idiomatically for each composer, there are qualities in Spivakovsky’s pianism that are consistently noticeable: an incredibly refined sonority (even when the piano is out of tune, as it regrettably is in one case); phrasing that is masterfully shaped by fusing dynamics, tonal colour, and timing; a rubato that breathes and defies bar lines but serves the architectural structure of the music without the rhythmic pulse ever being lost; voicing that is consistent to the highest degree (the only pianist I’ve heard able to voice with such exquisite and consistent clarity is Lipatti); unbelievably subtle and mastery of the pedal; and incredible digital dexterity (though he apparently had such thick fingers that he had to rely on unorthodox fingerings – as will be revealed when a filmed performance is eventually issued). He is, quite simply, one of the greatest pianists I have ever heard – quite rightly dubbed by Rose as ‘the greatest pianist you’ve never heard of.’

While this reading of the Chopin First Ballade is unfortunately slightly marred by some tuning issues in the upper register of the piano (we must remember that all of these recordings are practice sessions that were not meant to be permanent accounts of his playing), the recording features poised Romanticism at its best. Spivakovsky highlights often-ignored lines that were also featured in the playing of Josef Hofmann in his legendary Golden Jubilee performance, yet whereas Hofmann would often bring these voices to the foreground, Spivakovsky incorporates them into the entire fabric of the work, so that the musical tapestry is both seamlessly woven and richly textured:

Even a work as traditionally overplayed by amateur pianists such as Chopin’s Fantaisie Impromptu shines like the most elegant jewel – not that Spivakovsky holds back any emotion! Indeed, Jascha plays with unbridled and at times volcanic passion without any loss of precision or refinement – how gloriously arched and deep is his phrasing, how ebullient his rhythmic drive. A work that can easily come off as trite or quaint is given a reading of blazing intensity in its outer sections while the middle section is most lovingly phrased with a smooth lyrical legato and discrete pedalling, with particular attention paid to transitions (as always seems to be the case with Spivakovsky), although those who pay more attention to the tempo might not notice his exquisite subtlety in such moments.

Volume 3 is slated to include four Beethoven Sonatas, including Op.111, while we can also look forward to some glowing Schumann (Concerto without Orchestra and Carnaval) in later editions. There is a teaser of the former on the website, and here is a magnificent excerpt of the latter: the Chopin section of Carnaval, with truly remarkable breadth in the repeat:

Each work on the two issued discs receives a performance of extraordinary musical insight and power. The Bach is grand and noble, the Mozart clear yet profound, the Beethoven charming and inquisitive. Spivakovsky’s Chopin is expansive and impassioned (as has been heard above), his Brahms lush and rhythmically fluid, while his Debussy and Kabalevsky are both as idiomatic as you might hope (his Kabalevsky Third Sonata could displace Moiseiwitsch’s classic account).

Both compilations are available as digital downloads (complete with your own CD cover to print and musical scores) or as CDs to be delivered by mail order. You can find info about both volumes here [click Volume 1 or Volume 2 in the upper right corner to get details about each individual disc]; and you can order the first compilation here and the second one can be purchased here. I personally opted for the downloads to save time and money – I didn’t want to wait to hear this amazing playing!

Both compilations are available as digital downloads (complete with your own CD cover to print and musical scores) or as CDs to be delivered by mail order. You can find info about both volumes here [click Volume 1 or Volume 2 in the upper right corner to get details about each individual disc]; and you can order the first compilation here and the second one can be purchased here. I personally opted for the downloads to save time and money – I didn’t want to wait to hear this amazing playing!

While there are many pianists whose playing I adore, there are few for whom I hold unreserved appreciation, and Jascha Spivakovsky is now one of this small group. His highly individual signature – a gorgeous singing sound, with crystal-clear articulation, transparent and utterly consistent voicing, and magnificently forged phrasing – is almost immediately recognizable in the way that the unique fusion of qualities of Lipatti, Cortot, and Hofmann can quickly be perceived. Even if his playing at times can be so original as to raise an eyebrow – his almost pedal-free reading of the first movement of Chopin’s Second Sonata is highly unusual yet also intriguing and an approach worth considering (he told his son that he felt it was the best way to achieve the ‘Agitato’ called for in the score; I expected it to be a bit wilder but his more subdued, dry effect is fascinating) – it always has its own innate logic and is tremendously musical.

I simply cannot get enough of Spivakovsky’s playing and cannot wait for more performances of this superlative artist to be issued – I’ve heard excerpts of a Mozart Concerto broadcast that is outstanding and this and some more live concerto recordings are part of this planned series. This is some of the most arresting pianism I have ever heard and I cannot recommend these discs highly enough.

Comments: 3

Oustanding! Thank you very much, Mark Ainley!

What a pianist!!! My GOD!!! just incredible!!! Thank you so so much, Mark, for sharing him with us!!!

Great article on my Grandfather – I’m so happy he can be shared this way now.